The Three Worlds of Ballroom Dance

Social |

Competitive |

Exhibition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Which one is better? Yes, that question is intentionally provocative, and is easily answered. All three forms are valid, each enjoyed by their adherents for good reasons. But it's helpful to know how and why they differ from each other. As you'll see in the third section below, it's sometimes essential to know the differences. First, what is Ballroom Dance? "Ballroom dance" refers to traditional partnered dance forms that are done by a couple, often in the embrace of closed dance position ("ballroom dance position"). These include waltz, swing, tango, salsa and blues. "Ballroom dance" is the overall umbrella term, covering all three forms discussed on this page. Social dance forms are important. The earliest historical dance forms ever described in writing were partnered social dances. Many of today's performative dance forms, including ballet and jazz dance, evolved from social dance forms that came first. And today, noncompetitive social dance continues to be the most widely done form of dance in the world. The three worlds of ballroom dance share the same historical roots, similar step vocabulary and music, so the three forms are considered siblings, related by birth. Yes, siblings are known to fight, but they can also be mutually supportive. What is the essential difference between the three? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Your partner |

The judges |

An Audience | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Then looking closer at the differences... What are your audience's expectations?

What is your focus? |

What is your attitude? | • Flexibly adaptive. You value and accommodate to styles that are different from your own. • Styles outside of the official syllabus are usually considered to be incorrect.

What is your reward? | • The satisfaction of becoming proficient in a dance form. • Self confidence. • The satisfaction of becoming proficient in a dance form. • Self confidence. • The satisfaction of becoming proficient in a dance form. • Self confidence.

What is the attitude concerning mistakes? | • When a Follow does something different from what the Lead intended, he knows it's a valid alternative interpretation of his lead. • Social dancers are happy if things work out 80% of the time. And the other 20% is when most learning happens. • When a Follow does something different from what the Lead intended, he considers it a mistake, which is to be eliminated. • Competitive dancers work hard to achieve 100%. • For amateur performances, audiences mostly want to see that the dancers are enjoying themselves, so mistakes are generally accepted.

Are there standardized steps and technique? |

Is there a standardized style? |

Is there a fixed choreography? | Both Lead and Follow engage in a highly active attention to possibilities. An exception is West Coast Swing Jack and Jill competitions, with a partner that one has not danced with before. But improvised exhibitions occasionally exist in swing, tango, cross-step waltz and blues.

Do you make your own decisions? | Again, an exception is West Coast Swing Jack and Jill competitions.

|

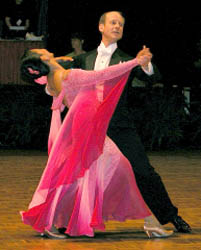

Difficulty of technique To state the obvious, competitive ballroom technique is designed for competitions. If dance technique is easy, judges won't be able to separate the good dancers from the very best. Therefore competitive ballroom technique is intentionally difficult, so that only the very best dancers can master it. It requires many years, and extreme focus, to master this technique. U.S. Ballroom Dance Champion Stephen Hannah said, "You must want to go to the very top and be the very best dancer. You must be able to use your time seven days a week without allowing any other influences to interfere." This is not a problem. Competition ballroom dance is also known as dancesport, and competitors in every sport train hard to win. It's work, and competitions are usually stressful. Conversely, social ballroom technique is intentionally easy. Dance partnering is challenging enough as it is, to coordinate one's movements with another person. And most people want to dance with their friends as soon as possible. Therefore social dance technique is intentionally expedient, so that dancers can focus on the connection to their partners instead of intricate footwork technique and a highly specified style. It's play, and well known to be effective stress relief. Repertoire of dances The repertoire of International Style ballroom dance (the dominant competition form) was last revised around 1960. The ten International Style ballroom dances are: Slow Waltz Viennese Waltz Jive (British swing) Cha-Cha Tango Paso Doble Slow Foxtrot Samba Quickstep Rumba Sixty years later, half of those (the second row) have mostly disappeared from recreational social dancing. Noncompetitive social dances are constantly updated. These include: Lindy Hop West Coast Swing East Coast Swing Hustle Nightclub Two-Step Cross-Step Waltz Rotary Waltz Country Waltz Viennese Waltz Polka Salsa Cha Cha Bachata Merengue Kizomba Social Tango Tango Argentino Blues Fusion and many more. The number of social dances increases each decade. Other social dances Not all social dances are partnered ballroom dances. Other social dance forms include hip-hop, breaking, line dances, international folk dance, contradancing, square dancing, grinding (yes, we need to include that), and informal permutations that defy categorization. This page focuses on the three worlds of ballroom dance, but acknowledges the many facets of social dance. For the first century of closed-couple dancing, only the first category of ballroom dance existed: noncompetitive social ballroom dance. This was the 19th century, the age of the waltz and polka, when "ballroom dance" meant precisely that – dancing in a ballroom. Furthermore, at that time, the term "ballroom" meant any room that was built for dance parties (balls), including small dance halls. What was the attitude of a ballgoer? An important part of the 19th century ballroom mindset, in both Europe and America, was selfless generosity, with an emphasis on enhancing the pleasure of your dance partners and the assembled company. "In general manners, both ladies and gentlemen should act as though the other person's happiness was of as much importance as their own." — Prof. Maas, American dance master, 1871

Another important part of the original ballroom attitude was a flexible mindset and adapting to your partner. The American dance master William DeGarmo wrote in 1875, "Gentlemen who acquire a diversified style easily accommodate themselves to different partners. No two persons dance alike. When their movements harmonize, this individuality is not only natural and necessary, but it pleasingly diversifies the whole."Fred Astaire wrote, "Cultivate flexibility. Be able to adapt your style to that of your partner. In doing so, you are not surrendering your individuality, but blending it with that of your partner." For noncompetitive social dancers, this original attitude of generosity, kindness and flexibility has never ceased, and continues in today's social dancing.

A primary motivation of the middle class is upward mobility. You can raise your position in life through the mastery of skills. The working class embraced the mastery of Sequence Dances, which led the Frolics Club in London to create the first judged competitions of ballroom dance in 1922, as a way to elevate one's social position through perseverance and hard work. This work ethic is still visible in competitive ballroom dance today.

Of the three forms, which one is best? It depends on you. Dancers usually have a preference for the one that especially suits their personality. Or someone may like the visual look of one of the performative forms, and want to dance in that style. It's important to know the differences, for the following three reasons: To recognize which form(s) best match your personality. Dean Paton believes there's an essential difference between social and competitive ballroom dance, and that different personalities are naturally drawn to one or the other. It essentially comes down to knowing yourself, and finding the right match for you. Quoting Dean, "We call your attention to these kinds of dancing because, unless you understand something of their differences, you could land on the wrong dance planet and be unhappy." Just try one, and see if it fits your personality and preferences. To avoid the unfortunate mistake of applying the rules and attitudes of one form to another. This isn't just an abstract differentiation — the repercussions can be serious. For instance, occasionally a ballroom dancer will pedantically insist that his partner conform to competitive stylistic details at an informal social dance, "You're doing it wrong. You have to do it my way," resulting in the contradiction of antisocial behavior at a social event. (See more on the "Sketchy Guys" page.) Conversely, socially adapting to your partner's mis-step at a competition may eliminate you from that round. Both forms are equally valid, within their own arena, but they have almost opposite attitudes. Some dancers do both social and competitive dancing, or all three forms, and some of them are wonderfully adept at knowing which attitudes are appropriate for each. At a social dance, they're friendly, spontaneously adaptive, and warmly supportive of their partner's differing style. Then they are rigorously correct and expansive when competing. They understand and respect the differences. To sharpen your ability to spot deceptive marketing practices. As the competition ballroom dancer Juliet McMains points out in her eloquent book Glamour Addiction, some (not all) ballroom studios attempt to change the minds of students who arrive wishing to learn social ballroom dance. She wrote: Primarily because teaching competitive ballroom dance has proved to be so much more profitable than teaching social dance, the industry rhetoric implies that social ballroom dancing is merely poorly executed DanceSport. Students usually embark on a social dance program with the expectation that they will take a few lessons, learn how to dance, then leave the studio in a month or two. From a business perspective, studios and teachers are deeply invested in altering this plan. If a teacher can sell a student on competition dancing, their student will have to spend years taking dance lessons to master the difficult competition technique.Dance studios know that most of their customers arrive seeking easygoing social dancing for pleasure, not the daily hard work to master competitive styling, so some (not all) studios attempt to give the misimpression that competitive ballroom dance and social dance are the same thing. Quoting McMains again, "Such attempts to emphasize continuity between these two groups, and downplay the chasm between social and competitive ballroom dance, represents a crucial apparatus of the Glamour Machine." Competitive ballroom dance is a perfect fit for those drawn to competing, so neither we nor Juliet McMains (who is a professional dancesport competitor) are criticizing competition ballroom dance, nor the honest studios that give their students what they're looking for. The point is that it's smart to be aware of the many differences between the three worlds of ballroom dancing: Technique Styling Standardization Difficulty of technique Choreography vs. improvisation The response to mistakes Repertoire of dances Adaptability Motivation Attitude Romance Have you noticed that this page hasn't stated the obvious yet? In the past, some of the primary motivations were the romantic pleasures and pursuits to be found in social dancing. Social dancing played a key role in courtship for the past six centuries. To quote Jane Austen, "To be fond of dancing was a certain step towards falling in love." (Pride & Prejudice). Most films that feature social dancing have been romances, from the Astaire/Rogers films to Dirty Dancing and La La Land. Today, seeking a mate is de-emphasized, and partner roles aren't necessarily gender normative. There are many other reasons to enjoy partnered dancing, but this page would have been incomplete without a brief mention of romance.

— Richard Powers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To recognize which form(s) best match your personality.

To recognize which form(s) best match your personality.