The Authentic Role of a Nineteenth Century Dance Master

Richard Powers

Does the group have a leader, similar to a nineteenth century dancing master? If so, here are three important questions.

1. Does your group do what nineteenth century dancing academies did, teaching classes and organizing balls?

Yes? Good.

2. Do the group members do what nineteenth century dancers did, performing dances from that time, in the attire from those eras?

Yes? Good.

3. Does your group's dance master perform the functions of a nineteenth century dance master?

Yes? Good.

No? Why not?

I am often surprised to see a group that only does the first two, but then stops there, thinking that re-creating the full picture of all three is somehow wrong. How can it possibly be wrong to let your dancing master perform the functions of a nineteenth century dancing master?

The role of a nineteenth century dancing master

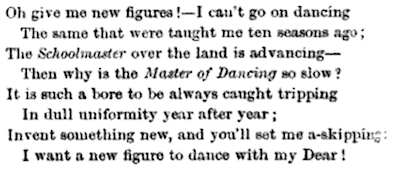

Teaching classes was only one part. Dance masters often created new dances and variations for their students. Their pupils regularly attended balls, grew tired of the same figures repeated each time, and wanted new figures to dance at the next ball. Thomas Haynes Bayly (1797-1839) captured this sentiment in his poem from around 1830.

Bayly was specifically writing about quadrille figures, and the subsequent stanzas of that poem described the tedium of La Pantalon, L'Eté, La Poule, Las Pastorale, and especially the Finale.

Finale and L'Eté are one and the same.

Finale and L'Eté are one and the same.In addition to learning figures from dance manuals and from other teachers, it was the job of the dancing master to create the requested new variations, like a new Finale figure for the original quadrille, since it was essentially a repeat of L'Ete. Most nineteenth century dance masters choreographed entirely new quadrilles for their dancers, like Joseph Hart's 49 sets of quadrilles. Or Hillgrove's Favorite Quadrilles, Hillgrove's Second Set, Hillgrove's March Quadrille, Hillgrove's Waltz Quadrille, Hillgrove's Social Quadrilles, Hillgrove's Royal Polka Set, etc.

Dance masters also modified existing dances, sometimes editing or deleting a figure of an existing quadrille. Did anyone say it's wrong to modify an existing quadrille? No. Hart's Lancers was a significant example of a modified quadrille, after Duval's Lancers. Then other dance masters created a Waltz Lancers, Diagonal Lancers, a Lancers for 16, Glide Lancers, Dodworth Lancers, Loomis Lancers, and so on. Modification was commonplace. See this page for quotations from dance manuals about the practice of eliminating one or two of the figures when dancing quadrilles.

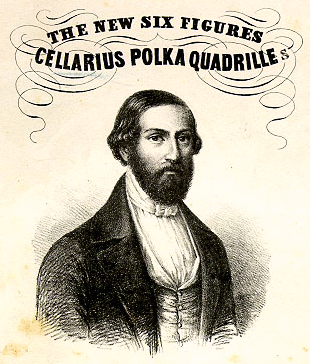

Sometimes dance masters created entirely new dance forms. Chivers and Markowski were especially notable for their innovations. Dodworth created a schottische in slow 3/4 bolero time. Cellarius created a waltz in 5/4 time, and then gave only one version, as "a mere suggestion," because he wanted others to come up with their own variations.

Here are only some of the many nineteenth century dance masters who created new dances and variations:

|

Thomas Wilson Duval of Dublin Joseph Hart Edward Payne Franz Anton Roller G. M. S. Chivers Henri Cellarius Charles Durang Carlo Blasis Thomas Hillgrove Eugene Coulon M. Markowski Edward Ferrero D. L. Carpenter Charles d'Albert Allen Dodworth |

|

There is also the distinction between a dancing master and a teacher. An academy's dancing master often created and modified dances, but the teachers at the academy only taught dances created by others. Allen Dodworth was a dancing master. His son Frank was a dance teacher at his academy. So if you are re-creating a nineteenth century dance academy (a historical dance group or school), decide whether your leader is a dancing master, or a dance teacher. Either choice is valid.

And today?

Today, some historians keep the dance master's role alive, continuing to perform these functions of the original dance masters, including occasionally modifying historical dances for their group. But others insist that one should only teach dances created by others, exactly as described in nineteenth century sources, with no modifications allowed. They understand that the original dance masters continually modified and created dances, but they would rather be a dance teacher than a dancing master. Everyone has their own preferences in recreating historical dance, and each choice is valid.

Oddly, some people believe that today's historical dancers can be as creative as the original dancers were, improvising polka variations or mazurka figures at a ball, but that today's dance masters should not be allowed to be creative in the manner of the original masters. Why allow one living process, and deny the other? It would be more consistent to either allow both, or prohibit both.

I'd like to clarify that I am not saying that historical dance teachers should create and modify historical dances. It's perfectly fine to choose the role of a dance teacher, and only teach the choreographies of others. The point is that both approaches are authentic and valid. Don't complain about anyone who prefers to take the other road. Both paths are correct and historically authentic choices.

How to do it

80% of my work is in exact dance reconstructions, without any modifications. But I also think we can occasionally engage in the authentic process of a nineteenth century dancing master, to keep that process alive. When I do this, I prefer to only use choreographic elements and traditions that were known to a nineteenth century dance master, from a certain year and locale. And I think the modification should be plausible, that is, having the same look and feel as the original creations, following the same conventions.

I don't recommend modifying a dance that is already in active repertoire among reenactors. We don't want to create confusion among ballgoers about which version to dance.

I haven't done many of these, but my modifications include my own version of a Triplet Galop Quadrille, which I created at the request of my Flying Cloud Academy students, and a short two-figure edit of Durang's Russian Mazurka Quadrille as a performance, because most audiences don't have the patience to watch four repeats, for each of five figures. My original creations include Romany Polka and the contra dance Moskwa.

Instead of following my guidelines for creating new work, I encourage you to develop your own approach. Do your own research, to explore how the original dance masters created their new variations. What were their philosophies and techniques? Research the choreographies of past dance masters, to better emulate their creative process. Then make your own choices.

It is important to clearly identify which of your reconstructions are unmodified, which are modifications, and which are new

creations. If you teach someone

else's reconstruction, always include this clarification.

It is important to clearly identify which of your reconstructions are unmodified, which are modifications, and which are new

creations. If you teach someone

else's reconstruction, always include this clarification.I wrote this paper for those who reenact historical dance, not necessarily for scholars who only live in the world of books and dissertations. If you re-create historical dance, in costume, you are essentially role playing. My point is that one role is that of a dancer attending a ball, and another role is that of the group's dance master. Both roles have their dynamic function. Both roles work together.

This paper focuses on reenacting nineteenth century dances, but it applies to earlier or later eras as well. Historical dance re-creation is a living process, as the original was. Keep the original spirit alive.