Following the fall of the Ancien Regime in 1789, social dancing became more natural and egalitarian.

Both clothing and dancing became less elaborate and restrictive as the rigid formalities of the

Baroque ballroom eased.

19th century social dance can be seen as three eras, each with its unique clothing, manners, music and dances:

The Regency Era

This term, referring to the English Prince Regent (1811-1820), is sometimes used informally to refer to the wider

period between 1800 and the 1830s.

In England and France, the most popular new dance of 1815 was the Quadrille, created from older French

Contradanse and Cotillon figures. The Quadrille was performed with a wide

variety of rapid, skimming steps, such as the chassé, jeté assemblé and entrechats.

English Country Dances, the Scotch Reel and Mazurka also featured intricate steps, and

added variety to an evening's dancing. These set dances, done in formations of

squares and lines, were joined by an unusual novelty performed by individual

couples: the Waltz, which had risen from peasant origins to society assembly

rooms. However the Waltz was more often discussed than actually danced at first. After

centuries of dancing at arm's length from one's partner, much of genteel society

was not ready to accept the closed embrace of the Waltz.

The flowering of the Romantic Era

While the Waltz received a great deal of criticism, as "leading to the most licentious of

consequences," it slowly made some inroads into the ballroom, aided by the occasional performance

by a notable society figure. Waltzing jumped ahead in acceptability when its inherent

sensuousness was tempered with a playful exuberance, first by the Galop and then by the

Polka. The Polka from Bohemia became an overnight sensation in society ballrooms in

1844, eclipsing the Waltz at the time. The Polka's good-natured quality of wholesome joy

finally made closed-couple turning acceptable, introducing thousands of dancers to the

pleasure of spinning in the arms of another. Once they tasted this euphoria, dancers

quickly developed an appetite for more. The Polka mania led to a flowering of other

couple dances, including the Schottische, Valse à Deux Temps, Redowa, Five-Step Waltz and

Varsouvienne, plus new variations on the earlier Waltz, Mazurka

and Galop. Meanwhile, the increasing trend toward ease and naturalness in

dancing had eliminated the intricate steps from the Quadrille and country dances,

reducing their performance to simple walking.

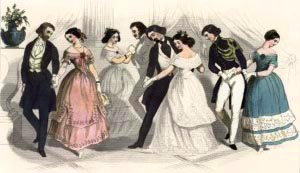

The overall spirit of this era's dancing (1840s-1860s) was one of excitement,

exuberance and gracious romance. The dances were fresh, inventive, youthful and somewhat

daring. Society fashions were rich and elegant, but continued an emphasis on simplicity.

By the 1850s, the ballroom had reached its zenith.

The High Victorian Era By 1870, social dances were

now those of one's parents, or even grandparents. The ballroom was slowly becoming the domain of high

society's Old Guard. As dancing become less exciting, fewer people devoted themselves to

mastering the full repertoire of dances. One-by-one, the

Mazurka, Schottische, Redowa and Polka began to fade. Dance masters formed

professional associations in an attempt to save their trade, but these organizations mostly

resulted in the standardization and codification of dance steps, which further dampened

the public's enthusiasm. Dance masters invented dozens of new steps in an attempt to

revive interest, but the public remained largely indifferent. High society balls shifted

their emphasis to the "German" parlor cotillion games, featuring expensive favors

(prizes). Middle class public balls saw the great variety of dances dwindle to just two:

the Waltz and Two-Step. By the end of the century, dancers were

ready for something completely different. After centuries of innovations created by European

leaders of society, they would not have guessed that the next wave of popular dance and music would come

from America's lower classes.