This discussion continues from this page on

the evolution of English ballroom dance style.

Schism over dance tempos

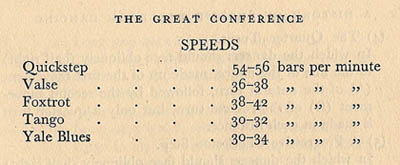

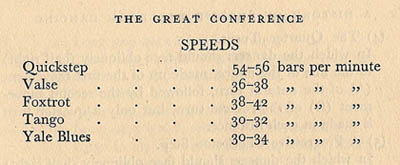

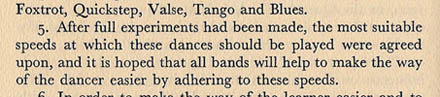

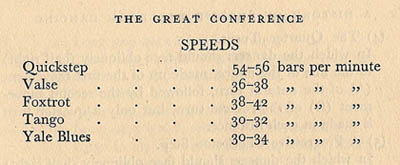

The 1929 Great Conference agreed to standardize ballroom dance music and its

tempos.1 Note the request for dance bands to adhere to these

tempos. Also notice the wide gap in tempos between the Foxtrot and Quickstep (fast foxtrot).

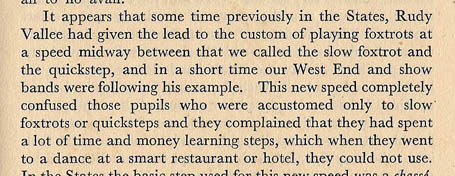

This standardization led to a problem, because the most popular dance bands in London were the American bands touring Europe,

playing dance music at all tempos, not just those specified by the

Great Conference.2

In the January 1934 issue of the Dancing Times, the Editor (Richardson) reported a bit of a revolt among dancers, against the standardized

steps and tempos:

The attempt very much in evidence during the past three months to find "routines" to fit music played at "unofficial" speeds or on crowded

floors is indicative of a certain amount of revolt against the idea that we must only dance Blues, Slow Foxtrot or Quickstep. For a

long time the dancers have said to the bands, "you must play your tunes at certain recognized speeds because the routines we have learned

and perfected can only be used at those speeds," and the bands have said to the dancers, "We must play the tunes at the speed intended by

the composer: it is most inartistic and wrong to play them otherwise. Moreover if you were real dancers, in the true sense of the word,

you should be able to alter your routines to fit any speed." Events of the past few months are symptomatic of the fact that a number of

people are coming round towards the band's point of view.3

The following month Mrs. Ralph Moody replied with a specific suggestion. Since competitions were the way that the

English advanced the art of ballroom dancing, she proposed holding competitions in the ability to adapt to the new dance music:

Could we not now put our dancers to the test of interpreting the rhythm and tempos as now being played? By this I mean, instead of

holding the hackneyed Foxtrot competitions, when the bands play a stereotyped tempo required to suit both the judge and competitor, let our

competitions take on a complete new line of thought. Ask the band leader to play for the competition at least four Foxtrots, each of a

different tempo. The test for the competitor being to adapt his movements and steps to the different tempos and the task for the judge

to select the best dancer, in the true sense of the word.

Real dancers, I consider, should always interpret the music; not say to the bands, "here are the steps I have learned, now

I want you to play some music that I can dance them to."4

Standardization of dance music

Instead, the Ballroom Associations took the opposite approach, dismissing those who wanted to adapt to the new music as "restaurant dancers."

There is a widening

gulf between the restaurant dancer and the competition dancer. The former does not take his dancing very seriously. Moreover

he takes more interest in the music. On the other hand the competition dancer takes his dancing very seriously. To him

the dance is everything: the music must be a slave of the dance – not a sister.5

The following year, 1935, in a quest to make the music a "slave of the dance – not a sister" the British World Champion Victor Silvester formed the

first British "Strict Tempo" orchestra to make sanctioned recordings for ballroom dancing, at the standardized tempos, which have continued to this day.

— Richard Powers

1 Richardson, Philip J. S. (1945). A History of English Ballroom Dancing. London: Herbert Jenkins Ltd. 78, 81.

2 Richardson, Philip J. S. (1945). A History of English Ballroom Dancing. London: Herbert Jenkins Ltd. 89.

3 Richardson, Philip J. S. "Ballroom Notes." The Dancing Times, January 1934 issue. London: The Dancing Times. 470.

4 Moody, Mrs. Ralph. "Fox-trot Speeds: Some Daring Suggestions." The Dancing Times, February 1934 issue. London: The Dancing Times. 588.

5 Richardson, Philip J. S. (1945). A History of English Ballroom Dancing. London: Herbert Jenkins Ltd. 89.

More thoughts and musings

Stanford Home Accessibility