The hidden story of the Apache dance, Part 2

Richard Powers

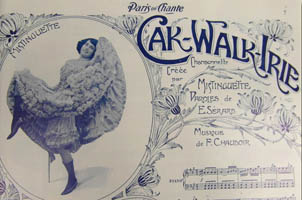

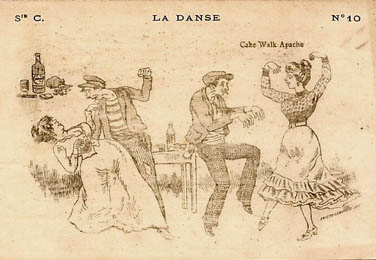

The hottest dance craze in 1900 Paris was the American Cake Walk. To quote a

Parisian magazine article (above right) about Mistinguette, "During last season there was not one concert, not one

music-hall which did not feature a Cake Walk."

After Mistinguette added the Cake Walk to her repertoire, she created specialized Cake Walks. But with

these, she only used the popular Cake Walk name, which was all the rage, applying it to very different kinds of dances.

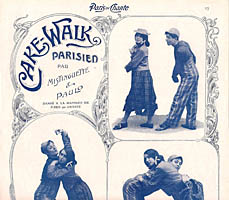

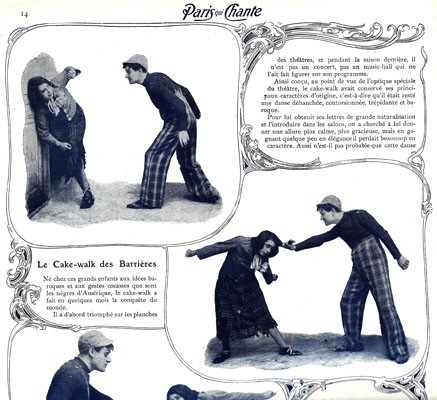

Mistinguette's "Cake-Walk Parisien" (far right) was a low-class bear-like hugging dance described in a 1903 issue of Paris qui Chante, a magazine of

popular music and dance. Like a circus act, this was a performed entertainment, usually for cabarets, not an actual

social dance.

Then, with a Mr. Paulo as her partner, Mistinguette took the low-class hugging a step further, and invented "The Cake Walk of the Barrières," which was

a mock fight-as-dance between a hooligan and a woman from the low-class Barrières (a region of Les Apaches). This new dance was

described, with photos, in the same 1903 issue of Paris qui Chante. The illustrations show the street thug

violently threatening the woman, and pulling her by her hair. The article described the dance as "vulgar

and amazing at the same time."

Like her Cake-Walk Parisien, this mock battle was an entertainment, a fiction. Mistinguette never stated that there was any

prototype of men choreographically abusing women in reality.

This dance also went by another name, La Valse Chaloupee, or Swaying Waltz, and later as La Danse du Pavé, Danse

Apache, and Valse Apache. As you recall, the reporter Authur Dupin coined the term Apache for this class of men in 1902,

so it took a year or two for that term to spread, becoming the popular name for the hooligans, then for this

dance. But it doesn't matter what the dance is called. It's the

concept that counts, and Mistinguette created it, five years before she partnered Max Dearly at the Moulin Rouge. And

of course Dearly, being in the business of self-promotion, claimed the successful new dance as his own.

Compare the first image from Mistinguette's 1903 original with the photo of Mistinguette's 1908

version with Max Dearly. I would say that Paulo, in Mistinguette's original version, appeared to be more threatening than Dearly.

In the postcard on the left we see that the name of Mistinguette's innovation quickly

evolved from the "Cake Walk of the Barrières" to the "Cake Walk Apache" with both forms illustrated —

the newer choreographed fight and the more traditional cake walk style. This postcard has a 1904 calendar printed on the back, and

calendars are usually printed at the end of the the previous year, so this illustration is probably from late 1903, still

five years before Dearly and Mouvet claimed to have invented the Apache dance. Soon

the Cake Walk fad was over, the name became passé, and only the Apache name and the domestic brawl version of the dance remained.

Now on to another important facet of the Apache.

The actress/dancer portraying the Apache's female partner was not a victim of abuse. She was proudly making

a statement, that she didn't have to remain in the cage of the Domestic Sphere, and furthermore, could stand

up to a man in a physical arena, a public physical arena. She willingly and enthusiastically entered that arena.

, from the 1935 film Charlie Chan in Paris.

Dorothy Applebee gives a sly smile at the beginning, then a big smile at the end — a smile

of achievement (at

least before the Charlie Chan murder plot kicks in). There is pride, physical strength and considerable skill in that

performance. And that's how Mistinguette created the dance, as a statement of independence, outside the role

that society preferred for women.

If you think that "outsider performance art" is a recent phenomenon, think a century earlier.

One might reply that the man also exhibited strength and skill, which is true, but the only dancer who is announced is

the woman, Mademoiselle Nardi, played by Miss Applebee. The male Apache dancer

remains anonymous. Not even IMDB lists

the dancer who played the male Apache, which wouldn't be the case if this

was truly a dance of man's dominance. In the Apache dance, the woman was the star.

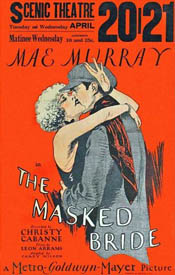

I could fill this page with illustrations of

the many examples of early Apache publicity that only mentioned the female dancer by name, including the apache in the 1925

film The Masked Bride which only mentions Mae Murray, and never her Apache partner, Buster Keaton. (Again, not even

IMDB mentions Keaton's role as the male Apache dancer.)

In the next photo of Apache dancers LaVerne and LaFayette, it appears that she's an unwilling victim of abuse,

being strangled, doesn't it? However the inscription that LaVerne hand-wrote on her photo reads, "To my

Mother and Daddy. From LaVerne." She's obviously proud of her dance.

If you watch any early film of the French Apache, you'll notice that the audience is always included in the

frame. The Apache was a cabaret act based on a fiction, not a re-creation of actual domestic violence, so

the audience is an important part of the picture. You'll also notice an equal number of women and men in

the audience, contrary to the myth that the Apache catered to male fantasies.

If you watch any early film of the French Apache, you'll notice that the audience is always included in the

frame. The Apache was a cabaret act based on a fiction, not a re-creation of actual domestic violence, so

the audience is an important part of the picture. You'll also notice an equal number of women and men in

the audience, contrary to the myth that the Apache catered to male fantasies.

In the early versions of the Apache, it didn't matter who "won" the brawl. The act aimed at portraying the

Apache thug as a cruel brute. But in later versions,

from the 1940's on, including Cole Porter's 1953 musical Can Can, filmed in

1960, the woman usually ended up turning the tables and winning the battle.

To conclude, I doubt if Mistinguette intentionally set out to change history, back in 1903. Mistinguette

may have come up with the idea of a mock fight-as-a-dance on a whim. She may have

been surprised that her mock fight grew into such a sensation. But her concept came from the center of a

strong and confident woman, so maybe Mistinguette wouldn't have been surprised that the dance ended up becoming a

stage for the empowerment for so many women at that time, when women were not allowed to stand for themselves in the Public Sphere.

© Copyright 2012 Richard Powers