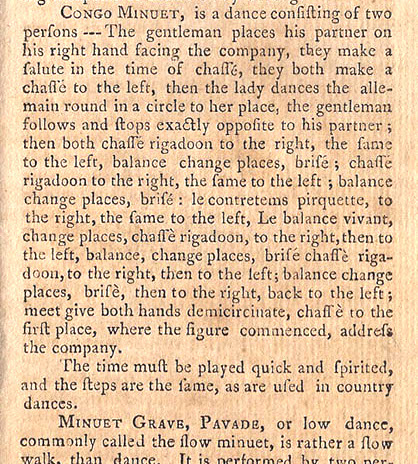

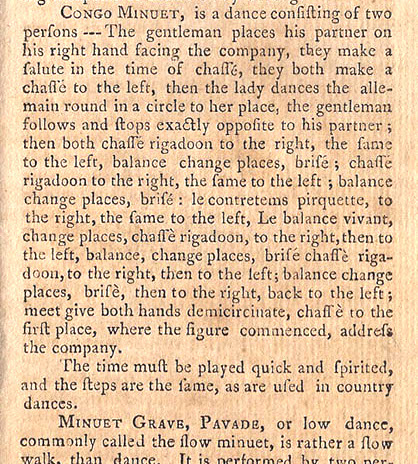

CONGO MINUET

A "quick and spirited" dance for two by Saltator, Boston, 1802

Richard Powers

About the dance (The reconstruction is below.)

This is a rare example of a complete choreography from the beginning of the 19th century. The description is from Saltator's A TREATISE ON DANCING, 1802, which is

probably the earliest American dance manual. A scan that I made of an original edition in my collection is available here.

The Congo Minuet combines the figures of the minuet (facing and crossing over) with the intricate steps and faster tempo of country dancing.

The description of this lively minuet precedes Saltator's description of a more traditional Minuet Grave. The full description is reproduced below.

Sieur Brives described a similar Menuet Congo in his 1779 NOUVELLE

METHODE POUR APPRENDRE L'ART DE LA DANSE SANS MAITRE, Toulouse, France. Congo Minuets

were mentioned in John Davis's TRAVELS OF FOUR YEARS AND A HALF IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

DURING 1798, 1799, 1800, 1801 AND 1802, and also by Moreau de Saint-Méry (1801) and several other sources around the same time. The Minuet d'Hyger in the

DANCE BOOK T.B., 1826 was a Congo Minuet in form, if not in name.

John Davis referred to Congo minuet as a genre of dance, not a specific title, when he wrote, "there was nobody that could face him at a Congo minuet; but Pat Hickory

could tire him at a Virginia jig."

Neither Saltator nor Brives explained the significance of "Congo," which has raised much speculation. The Congo Minuet may have come from the Colonial French West Indies in the 18th century,

or not. Regardless of its origin, the dance appears to have spread to several countries by the beginning of the 19th century.

The Congo Minuet is essentially one simple concept: performing the ancient minuet with the latest fashionable footwork—chassés, rigaudons, brisés and the new balance steps.

The idea of performing an old dance form with the latest steps is a rather obvious innovation, and has thus happened many times over the centuries. For example, dance masters in the 1840s

executed the old waltz with newly fashionable mazurka steps, thus creating a host of mazurka waltzes, like the polka mazurka and redowa. There are many other examples, because it's human nature

to want to modify older social dances to be up-to-date. If one dancer had not thought of the idea of performing the old minuet with the latest popular footwork, another likely would have, and possibly did, in 1826.

Since the thought of doing an old dance with new steps has happened many times in history, the Minuet d'Hyger in the Dance Book T B., 1826, might have been the result of another dancer coming up with this obvious

combination independently, without knowing about the earlier Congo minuets. And since the old minuet and the newer country dance steps were both from Western Europe, a Congo

connection isn't necessary to think of combining the two. We can speculate that there was indeed a Congo connection, because of the name, or we can wonder if the name was used because it sounded exotic, or for

some other reason. We can never know with certainty, one way or the other, until a newly discovered primary source answers the question.

● ● ● ● ●

Saltator seems to have learned this dance in person, rather than from the earlier Brives description. There are many differences in Saltator's Congo Minuet;

Saltator's Minuet Grave is quite different from Brives'; and Brives' other dances don't appear in Saltator. And Saltator seems to have heard the terms

instead of reading them. If Saltator had read the French books, he would have copied the same Rigaudon spelling. Instead it seems that he heard the word,

and wrote it as Rigadoon. Same with his "Le Pas et Basque" instead of Pas de Basque. And his method of describing steps is unique, not borrowed from any previous dance manual.

The greatest strengths of this description are: 1) It records the complete sequence, from opening salute to closing address, rather

than simply offering an excerpt or abstraction;

and 2) each term in the description, without exception, is further explained elsewhere in Saltator's book.

On the other hand, the step descriptions are rather vague, merely listing foot positions, with the frequent use of the term "hop." Furthermore,

a foot position does not mention whether it is stepped with weight or pointed without weight, or whether it walks, glides, raises into the air,

dips into plié, leaps, brushes, or closes to an assemblé.

The use of the term "hop" is quite different from today's definition, but is consistant with occasional 18th/19th century usage, merely implying that an elevation of the body occurs with a step, without

specifying whether the elevation occurs before, during, or after the adjoining steps, or whether a hop is executed by itself. For example,

using today's terminology, "Left foot 4th hop right foot 3rd" would imply that you step forward L, then hop on the L, then close R to 3rd

position (three movements). But in the earlier tradition, this is Saltator's way of stating that after stepping forward L, you

should close R to 3rd with an elevated movement, such as a jeté or assemblé (for a total of two movements).

Although Saltator does not specify step timing or passage duration, he does tell us how many movements are in each enchainement. The above

example, occuring at the end of a passage, was specified as two movements, not three. This common cadence is therefore probably a

step-assemblé, and prefigures the jeté-assemblé cadence of the later Regency era. A few decades later the "Hop Waltz" similarly

meant an elevation during the first step of a waltz, which would later be called a jeté instead of "hop."

When Saltator calls for the dancers to chassé, it is tempting to interpret this as a single chassé step (step-close-step, 1 bar). However

when investigating the use of this

term throughout the entire choreography, it becomes clear that his usage of chassé actually means a chassé sequence

(chassé–step–assemblé, prefiguring the later chassé–jeté–assemblé, 2 bars).

Saltator's dance manual would have been based on the technique and traditions of the previous thirty years, rather than forshadowing the

evolutionary changes of the Regency era. His choice of steps, their terms and spellings, and the patterns of enchainement are all

similar to European dance manuals, dance dictionaries and cotillon collections dating from 1760 to 1800. Therefore the Congo Minuet

is reconstructed using concordances and step descriptions from Gallini (1760s and 1770s), Magri (1779) and Compan (1787),

rather than using sources dating from the following decades.

The Reconstruction

The bold lines quote the original description.

I. - Introduction

The gentleman places the lady on his right, facing the company, waiting. [4 bars] Most sections of this choreography fit 16 bars

of music, as expected. However, the opening passage is shorter, implying that the dancers wait during part of the opening music before beginning. Saltator's

mention of addressing bows "facing the company" implies that this choreography was intended to be an exhibition dance performed for

an audience, possibly composed of peers at a ball.

They both make a salute to the company in the time of chassé [2 bars]

• Step to 2nd away from partner; • close to 3rd; • lady pliés and man inclines; • rise.

See the note in the paragraphs above about "chassé" actually meaning a chassé sequence (chassé, step, assemblé).

They both make a chassé to the left side [2 bars]

• Glide L to 2nd, close R to 3rd behind, glide L to 2nd; • close R to 3rd above; • assemblé L to 3rd

above.

Note: The step before the assemblé is not a jeté.

The lady dances the allemain around in a circle to her place, the gent follows and stops exactly opposite to his partner. [8 bars]

This is the least clear section of the entire dance. My guess is that the lady travels in a circle around CCW and back to her place with Saltator's

Allemain step. The Minuet d'Hyger (a Congo Minuet by another name) in the Dance Book T B. 1826 is illustrated with

diagrams. The opening passage has the lady circling around CCW, but ending in a diagonal corner instead of back to her starting place, exactly

opposite her partner, in Saltator's version.

The specification of standing exactly opposite one's partner is a distinguishing characteristic of Saltator's Congo Minuet, different from the diagonal corners in Brives and the

Dance Book T B. 1826.

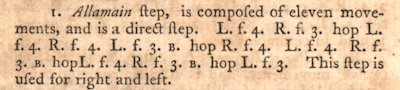

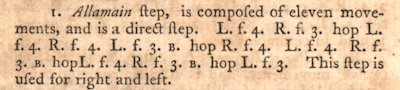

Saltator's Allamain step is not at all clear but seems to be a series of chassés where the third step of each chassé is a jeté, probably a small one

because there is no time for a large jeté. Saltator explains on page 56 that L. f. 3. B . means stepping L to third position before (in front), even though

closing behind is easier. It could be a typo but this reconstruction keeps it before, as described.

• Glide L to 4th, • close R to 3rd in front, • small jeté L to 4th [1 bar]. Repeat opposite [1 bar]. Repeat L [1 bar].

• Close R to 3rd in front • Jeté L closed to 3rd position, presumably in front [1 bar].

Saltator's step descriptions most often begin with the left foot, as here, then later in his book when he gives choreographies of dances,

steps may begin on whichever foot is appropriate for the moment. In this case, the Allamain step works much better beginning on the

right foot, for both commencing and finishing the figure. Then repeat the entire sequence beginning L (because

the L foot is then free). The step is more easily learned in class than from this written description.

The path of travel is a large CCW circle, starting toward the right diagonal, probably with the gent following behind. The lady covers half of the circle

with one of Saltator's Allamain sequences, then continues around to place with another sequence. (It's not possible to circle around to place with only one

Allamain sequence, and performing two Allamain sequences completes a 16 bar section of music.) The gent travels halfway across the set, to end in the center of the side opposite to where he began.

II. Chassé Rigadoon

Both chassé to the right side and rigadoon (rigaudon). [2 bars each, 4 bars]

Chassé sequence as above, but to the right side. Then do a Rigaudon to the left side: Preparation: Plié

in 3rd, L behind. • Spring up on R, extending L to 2nd, and land on R in plié, holding L in 2nd; • spring

up on R again and close L to 3rd above, at the same time cutting the R out to 2nd; • close R to 3rd above without a

spring; • assemblé L (around through 2nd) closing L to 3rd above.

Reconstruction note: Saltator's rigadoon is unusual among rigaudons of this period—an especially unsatisfying series of closings only

to third position. One may feel free to dance this version, found in my download of Saltator's book, but this reconstruction opts

for the more satisfying mainstream rigaudon. It's a minor point, either way.

The same to the left.

Chassé sequence to the left side then rigadoon to the right side. [4 bars]

Balance [4 bars]

Any individual balance step, "compounded ad infinitum, and may be graced with various flying movements of the feet...

changes of attitude, half turns, and many other additions incapable of description, which can only be learnt by imitation,

or the offspring of genius." Saltator's Balance suggestion has ten movements, beginning on the left foot.

His manual includes a description of a Pas de Basque ("Le Pas et Basque").

Suggested balance: one Pas de Basque (step side L, cross R over L, uncross; repeat opposite) then Balance en Carré

(step or jeté forward L, side R, back L, assemblé R behind L).

Change places [2 bars]

Advance with 2 chassé steps, L and R, passing right shoulders.

Brisé [2 bars]

Cast off to the left with • L to the left side (2nd); • jeté R to 3rd before; • close L to

3rd above; • assemblé R 3rd above.

Saltator's Brisé is different from the later Regency era Brisé.

Chassé rigadoon to the right; the same to the left [8 bars]

The same as above.

Balance [4 bars]

Possibly use a second balance step.

Suggested balance: He does chassé L fwd passing her R shoulder, 2 glissades side R as if a dos-a-dos; turns

right and chasse R, glissade dessous L then assemblé. She does Pas de Basques L & R, Balance en Carré L, all

in place.

Change places, and brisé [4 bars]

The same as above.

III. Contretems Pirouette

Le contretems to the right side and pirouette [2 bars each]

Le Contretems, the cross steps: • Close L to 3rd behind; • glide R to 2nd; • L 3rd behind; •

R to 2nd; • L 3rd behind; • R to 2nd; • L 3rd behind.

La Pirouette, the turning round: • Assemblé R to 3rd behind (passing through 2nd); • pirouette

to the right on both toes; • jeté on R in place; • jeté L before.

Note: "pirquette" in the original

description is no doubt a typographical error, perhaps a typesetter picking the wrong character. "Pirouette" is spelled

correctly when Saltator describes the step in detail.

The same to the left [4 bars]

Contretems to the left side and pirouette.

Le balance vivant [4 bars]

Any individual balance step. Saltator's Balance Vivant suggestion

has 13 movements, beginning on the left foot.

Suggested balance: a casting off version of what the gentleman did before, beginning L and casting over the left shoulder.

Change places, brisé [4 bars]

The same as above.

IV. Chassé Rigadoon, to both sides, again

Exactly that—repeat Part II, perhaps with different balance steps.

An exhibition version can skip this repeat of Part II.

V. "Then to the right, back to the left"

This possibly means do the Contretems Pirouette again, since that's next after the repeated Chassé Rigadoon,

but it's unclear. An exhibition version can skip this.

VI. Conclusion

Meet, give both hands and demicircinate [4 bars]

Advance to meet partner with the chassé sequence L, offering both hands. Then the lady turns half-round in a

circle (the gent only turns one-quarter) to the left with the chassé sequence, ending facing the company.

Chassé to the first place where the figure commenced [2 bars]

Facing the company, do the chassé sequence to the right side.

Address the company. [2 bars]

Videos.

Here is a video of this reconstruction, from a class in Russia.

Here are videos of reconstructions by Tim Lamm and Paula Harrison of the 1779 Brives Menuet Congo and

1826 Minuet d'Hyger.

Music. Any country dance tune will work, as long as it predates the 1802 description. I chose the old English country dance tune

Petticoat Wag (which continued to

be used in country dancing, sometimes under a different name, like The Taylor's Daughter).

Many thanks to Dmitry Filimonov and Tim Lamm for their suggestions in refining this reconstruction, from my original 1990 version.

More dance descriptions

Dance music discography, classes, dance thoughts and more on the Home Page

Stanford Home Accessibility