The Life of a 1950s Teenager

The Life of a 1950s Teenager

Richard Powers

The Life of a 1950s Teenager

The Life of a 1950s Teenager

● Boy's hair touching the ears wasn't allowed, punishable by expulsion from school.

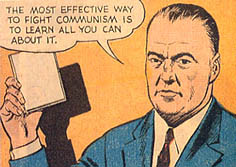

World War II had ended but the world felt far from safe, between the new war in Korea, frightening talk of the

Communist menace, and the threat of nuclear war. If there was a national priority in America in the 1950s, it

was to create a safe, secure, calm and orderly community in which millions of post-war Americans could start a family.

First phase: marginalization. Sandwiched in between the generations of new postwar families and their boom of babies was a generation of teenagers.

Teens were marginalized by the adults, who didn't want to be bothered with the very different values of teenagers.

There were a few television shows aimed at young children, nothing for teenagers, and nothing on the radio speaking to teen

life. Teenagers felt left out, ignored, disenfranchised.

Then the teens started to hear music about their world — songs about high school sweethearts, wild parties and

fast cars, sung by other teens. They were hungry for some recognition of their generation, some validation, and

when it came, they embraced it. Momentum started to build as this generation developed their own image and style, combined

with the purchasing power of an increasingly influential demographic. The word "teen-ager" was newly coined at this time.

Then the teens started to hear music about their world — songs about high school sweethearts, wild parties and

fast cars, sung by other teens. They were hungry for some recognition of their generation, some validation, and

when it came, they embraced it. Momentum started to build as this generation developed their own image and style, combined

with the purchasing power of an increasingly influential demographic. The word "teen-ager" was newly coined at this time.

Second phase: condemnation. With the increased teen presence came disapproval, as marginalization and indifference turned into active

condemnation of teenagers by parents and local authorities.

Teen dances were shut down, rock'n'roll records were banned, and students were expelled for a

multitude of rule infractions.

There have always been inter-family conflicts between parents and their adolescent children, but

this cultural division was larger. A significant proportion of the adult generation disapproved of the values and lifestyle of the teens,

and were doing something about it, including setting new rules, restrictions and prohibitions.

● Most girls weren't allowed to wear pants, and boys weren't allowed to wear blue jeans. Even progressive Stanford University

prohibited the wearing of jeans in public during the 1950s.

● The new slang bothered most adults. It was part African American, part beatnik and part street

gang... an offensive combination in the eyes of the status quo.

● There was alarm about teens dating and "heavy petting." Any talk about sex was taboo and could be punishable.

● Many parents were worried about their daughters adoring black rock musicians, fearing the possibility of racial commingling.

● Hot rods were considered dangerous. All it took was a few fatal accidents and the other 99% of the custom cars

and hot rods were considered a menace to public safety.

● Dancing to rock'n'roll music was often banned, with school and teen dances shut down.

John McKeon recalled,

"What I remember most about the 50s were rules. Rules, rules, rules... for everything. Rules about clothes —

which clothes you could wear when. Rules about church. Rules about streets. Rules about play.

"The dance rules were different. Dance with girls and hold this hand, but then... you could do whatever you wanted

to do! Dance looked like freedom. The only freedom this kid knew."

The older generations were especially worried about "juvenile delinquency." Yes, some teen violence and street gangs did exist,

and those instances were widely publicized in newspapers and magazines. But for most teens, this didn't mean dealing in street drugs

or drive-by shootings, but rather using street slang, souping up a hot rod and talking back to parents.

Rock'n'roll music was attacked on all fronts, with records banned and smashed. Radio DJs were ordered not

to play certain songs; rock singers (especially Elvis) were condemned; and the career of rock promoter Alan Freed, the

man who named the music rock'n'roll, was destroyed by a government investigation.

To quote Michael Ventura, Gary Stewart and Billy Vera, who were there:

For one thing, for us white kids, the real '50s was only the latter half of the decade, because we didn't have

rock'n'roll until well into 1955, and in terms of popular culture the decade would hardly be worth mentioning without

rock'n'roll. For another, the feel of the time has not only been forgotten but also erased. And there's no way to

grasp the subversive force of this now-innocent-sounding music unless you can feel a little of what it meant to be a

kid hearing it as it was played for the first time.

For one thing, for us white kids, the real '50s was only the latter half of the decade, because we didn't have

rock'n'roll until well into 1955, and in terms of popular culture the decade would hardly be worth mentioning without

rock'n'roll. For another, the feel of the time has not only been forgotten but also erased. And there's no way to

grasp the subversive force of this now-innocent-sounding music unless you can feel a little of what it meant to be a

kid hearing it as it was played for the first time.

It was music that was made for teenagers and scared the hell out of adults; it was taboo-shattering music about–gasp–sex

and racial commingling. That's why records were burned, censorship laws were passed, and some lives were ruined.

Because this was the devil's music, and it was threatening the status quo.

But you couldn't stop anything this real. It hit you where you lived. It belonged to the kids and only the kids.

It set them apart. It gave them something to believe in. Rock'n' roll was their joy. It was their freedom. It is

still so today.