Teaching Tips

Some dance pedagogy guidelines by Richard Powers

First, two disclaimers:

1) In giving these guidelines, I don't wish to convey an impression of superiority over any other instructor. We're all working on becoming more effective teachers and we all have room for improvement.

2) These are suggestions, from my observations over the past 40 years, not absolute rules. Some of my approaches may differ from the ideals of other instructors, as you might expect.

And two short observations:

1) Not all of the following guidelines and suggestions are essential. I've seen teachers miss some of these guidelines by a mile and still have an effective class, leaving their students satisfied and even delighted.

But some of these guidelines are especially important, mostly common pitfalls to avoid. So I've labeled some of my guidelines as

which means essential, in my opinion. (The most important suggestion here, halfway down this page, has a triple arrow.) Failing to do these may cause a negative impression or confusion in your class.

But most of these guidelines are merely recommendations. They may make a good class better, but omitting them won't hurt a good class.

which means essential, in my opinion. (The most important suggestion here, halfway down this page, has a triple arrow.) Failing to do these may cause a negative impression or confusion in your class.

But most of these guidelines are merely recommendations. They may make a good class better, but omitting them won't hurt a good class.

2) This page is long, and some of the best suggestions are toward the end. So you may want to read this in daily installments.

The sections below are:

Overview

Your lesson plan

Students' comfort zone

Teach with your whole mind

Timing of a class or workshop

Presentation of yourself

Your choice of words

Team Teaching

Pace of the class

Teaching experienced dancers

Aging teachers and/or students

Music

Spatial arrangement

Miscellaneous

THE OVERVIEW

Don't forget the big picture. In preparing for a class, we tend to get caught up in the smaller details of the steps and patterns, focusing on

the how and forgetting the why. So teachers often find they've finished the class without addressing the larger picture:

Don't forget the big picture. In preparing for a class, we tend to get caught up in the smaller details of the steps and patterns, focusing on

the how and forgetting the why. So teachers often find they've finished the class without addressing the larger picture:

● What do your students want to get out of the experience?

● Why are they taking your class?

● How is this dance relevant to their lives?

See your class from their perspective, to meet their needs.

The other half of the big picture is about the dances you're teaching:

● What is the essential quality or attraction of a particular dance?

● Who dances it, and why?

● In what way is the dance fun? (Too many teachers are so serious about improving their class that they end up marginalizing fun.)

● Why is this dance significant?

I know you could answer those questions when you stop to think about it, but I've found that if you think through these questions immediately before a class, you'll notice a remarkable improvement in the success of that class.

Why does this work? Because if you review these basics and ideals to yourself right before your class, then all of your spontaneous ad-libbed comments will tend to point toward the big picture, and help shape it. This cognitive approach to teaching supplements the linear approach (your lesson plan) in important ways. This pre-class mental review is like putting surgical instruments out on a tray before an operation. If the questions above are freshly reviewed in your mind, the answers will more readily occur to you during your teaching.

THE GUIDELINES

Take charge immediately in a direct, friendly, assertive way. Don't pussyfoot. This is important for new teachers, who are sometimes meek and tentative.

Take charge immediately in a direct, friendly, assertive way. Don't pussyfoot. This is important for new teachers, who are sometimes meek and tentative.

Don't start a class with a lecture. Get them moving right away.

Don't start a class with a lecture. Get them moving right away.

Know your audience. Different groups require very different approaches, depending on their dance experience, age range, preferred dance styles, and whether they wish to use your material professionally or recreationally. If you're traveling to a new group, ask your workshop sponsor many questions about their participants ahead of time, so you arrive prepared.

Know your audience. Different groups require very different approaches, depending on their dance experience, age range, preferred dance styles, and whether they wish to use your material professionally or recreationally. If you're traveling to a new group, ask your workshop sponsor many questions about their participants ahead of time, so you arrive prepared.

Take detailed notes on every class you teach, including which concepts (like partnering tips) you mention. When we brainstorm a lesson plan for the first time, all of the details are freshly in our mind during the class, and it goes well. But when we teach that dance the next time, perhaps a year later, most of the details, and how we broke them down, and which concepts we mentioned, have faded from memory. That's when you'll be glad you took detailed notes.

Take detailed notes on every class you teach, including which concepts (like partnering tips) you mention. When we brainstorm a lesson plan for the first time, all of the details are freshly in our mind during the class, and it goes well. But when we teach that dance the next time, perhaps a year later, most of the details, and how we broke them down, and which concepts we mentioned, have faded from memory. That's when you'll be glad you took detailed notes.

Update your notes. Immediately after your class (or as soon as you can) note (1) what worked especially well, (2) what didn't work as well, and (3) what you would have done differently, now that you have the benefit of hindsight. If you have a written lesson plan, you can quickly note how your class differed from the plan (I use a red pen) — crossing out the steps or details you didn't get to, and noting what you added at the spur of the moment.

Take as many other classes as you can, closely observing what other teachers do that is especially effective or problematical. Take notes on your observations.

Take as many other classes as you can, closely observing what other teachers do that is especially effective or problematical. Take notes on your observations.

Your lesson plan

Plan out every aspect of your class:

Plan out every aspect of your class:

What you're going to cover,

in what order,

how you're going to break it down,

how long you're probably going to spend on each part,

how the elements will relate to each other, and to material previously covered.

This includes developing back-up plans. What kind of additional material should you prepare in case the students turn out to be mostly experienced quick-studies? What if they're slow-learning non-dancers? What if they're a mixture of the two in the same class? And don't forget to bring music for teaching those back-up plans.

This includes developing back-up plans. What kind of additional material should you prepare in case the students turn out to be mostly experienced quick-studies? What if they're slow-learning non-dancers? What if they're a mixture of the two in the same class? And don't forget to bring music for teaching those back-up plans.

Reminder for the following few pointers: • means the suggestion is important, but not critical.

I recommend teaching by iteration, teaching the basic framework and weight-changes first, then shaping and embellishing it to achieve the final version. This gives your students' "muscle memory" a chance to build itself from its components, and also provides a logical concept and clear structure for the student mind to grasp.

Possibly throw them quickly through a step first, to see who catches it easily. Then break it down to an easier framework and build it back up. This way, they see the final step quickly before perfecting it, and they see the context of the step.

For confirmation of that last point, here is recent student feedback from my Stanford course evaluation page: "I like how Richard lets us 'try out' a figure before actually teaching us the steps, so that we understand them conceptually."

I sometimes take this approach a little further, demonstrating a step then asking the students to "fake it" once before I teach it. When they approximate it, they'll discover the tricky spot or stumbling point, and thus will watch for it more closely when you teach it. This gets them to ask the important questions, and for them to want to know how it goes, before you give them the answer.

Another benefit of the iteration process is seen in mixed-level classes. I encourage the beginners or slow-learners to remain at the level of detail that feels comfortable to them, as I continue adding more details for the more advanced dancers in the class. And I assure them that the further iterations and style pointers are optional, for those who may want them.

The iterative process works especially well when teaching partnered dances. If you teach the unadorned foundation version first, then a slow-learners who didn't master the next detail can continue functioning at the basic level, while the partners in their arms add the further details. They have a chance of staying in their comfort zone, which is important for their absorption on new material. This way, they aren't apprehensive about messing up their partner with their slower pace of learning.

Here's a little more on students' comfort zone, because I don't want to speed by this important point. Your students will reach their optimum learning pace if they're just a small, reachable step beyond their comfort zone — enough to be stimulated and motivated, but not to the point of feeling pressured or stressed.

Here's a little more on students' comfort zone, because I don't want to speed by this important point. Your students will reach their optimum learning pace if they're just a small, reachable step beyond their comfort zone — enough to be stimulated and motivated, but not to the point of feeling pressured or stressed.

When students are pushed out of their comfort zone, they emotionally put on the brakes. Learning stops. Besides, if they find themselves thinking, "I don't feel good in this class," they probably won't return to your next class.

Clarification: "Comfort zone" does not equal "comfortable," as in lazy. It does take effort to improve, and students enjoy challenges. The ideal level of challenge

is at the high end of a student's comfort zone. The point is to avoid pushing your students beyond that point, to stress or despair. That's when learning stops.

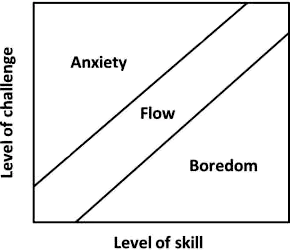

This is similar to Mihály Csikszentmihályi's Flow State, when the level of challenge matches one's skill level. Optimal learning occurs in the upper range of the

Flow State, not in boredom or anxiety.

Discomfort can also be cultural. Students from Asia or India often feel uncomfortable with a close embrace in couple dancing or sustained direct eye contact. Young women also tend to be uncomfortable with a close embrace. I suppose you could dismissively tell them, "Get over it," but they'll learn better, and stay in your class, if they're not pushed out of their comfort zone. If you feel that close embrace or direct eye contact is essential to your dance form, they may adapt to it in time — but only if they stay in your class.

Awareness of your students' comfort zone is important. If you're feeling overwhelmed by all of these teaching tips, just work on this one point

for now. Closely monitor your students' progress, for the perfect balance between boring and stressing them. Monitor the pace of the average of the group, not worrying too much about the few who got it instantly, and the few who are struggling (more on that later).

In a related point, never EVER lose your temper in class. Period. No exceptions. There are so many reasons why this is critical that it should be too obvious to require explanation. Most of the reasons have to do with losing control of the class. And losing control of yourself. (How can they expect you to control the class if you can't control yourself?) And thus losing their respect. Your anger will also hinder their learning pace by adding anxiety to the class.

In a related point, never EVER lose your temper in class. Period. No exceptions. There are so many reasons why this is critical that it should be too obvious to require explanation. Most of the reasons have to do with losing control of the class. And losing control of yourself. (How can they expect you to control the class if you can't control yourself?) And thus losing their respect. Your anger will also hinder their learning pace by adding anxiety to the class.

I am often asked for a formula of how to break down a dance in order to teach it. Of course there are no general answers – each kind of dance and step is too different for one formula – but here is a specific tip which I find effective:

You may be so adept at a dance that you no longer remember how it might be difficult for a beginner to grasp. So make yourself clumsy. Make your feet heavy and sluggish, almost drunk, then observe where you stumble. What are the basic weight changes and articulations that make it work better? I find that this helps me come up with a plan to teach that step, and helps me break it down into its elements, beginning with the basic weight changes.

Similarly, when you're teaching beginners, remember what aspects were tricky a long time ago when you were a beginner. See a dance through a beginner's eyes. Some of the worst teachers I know are the most adept dancers, because they don't know where the difficulty can lie for a beginner (because everything is easy for the adept teacher) so they don't know how to tell their students to get past the stumbling blocks. But hopefully you can remember what made a difficult step easier for you when you first learned it.

Another way to find the beginner's mind is to learn the steps you're teaching in mirror-image, using opposite feet and turning in the other direction. This makes it new to you. You may discover parts which you thought were easy, that are actually tricky for a beginner.

Appeal to visual, mathematical, auditory and kinesthetic learners by describing the same step in several ways.

Appeal to visual, mathematical, auditory and kinesthetic learners by describing the same step in several ways.

Some people learn better with specific details to master, while others need to grasp the overview gestalt of what the dance, step or pattern is all about. You will have both detail and concept-oriented people in your class – both left brain and right brain thinkers – so include details and concepts to reach both kinds of students.

Some think visually, so give them visual imagery, maybe drawing patterns on a white or blackboard (pictures and diagrams, not words). Some are more mathematically inclined, so specify how far you turn or step. For the kinesthetic thinkers, describe how the step feels when it's done right.

Don't slow down the class with these alternate approaches. Keep them moving. But since they have to repeat the steps to practice them, you can describe the same step in several ways while they're practicing it.

If you'd like to read more about this, look into Howard Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences

If teaching partnered couple dancing, always have one track of your mind on the Follow role. Many teachers make the mistake of teaching an entire session only addressing what the Lead role does, without offering many suggestions, advice or secrets for Follows to improve their dancing.

If teaching partnered couple dancing, always have one track of your mind on the Follow role. Many teachers make the mistake of teaching an entire session only addressing what the Lead role does, without offering many suggestions, advice or secrets for Follows to improve their dancing.

Repeat important ideas throughout a class or course, maybe in a different way each time. Saying something once doesn't mean that everyone will

truly hear it, or be ready to understand it. This is especially true in a dance class, where students are often internally processing

kinesthetic information instead of listening to you, or maybe still working something out a partner. Then, after the second or third time you say it, Aha!, the light bulb will go off.

Some teachers recommend that you teach the most significant style first, and minor stylistic variations later, because people have the greatest retention of their first-seen version of any dance.

Possibly teach the most difficult step early in the class (after covering the basics) while the dancers are the freshest. This also allows a difficult step to stay in the memory the longest and be practiced the most.

If a sequence ends with the most difficult step, you may be setting your class up for frustration. You don't want your students to hit that mess when they're the most tired and their brains are full. So maybe teach the final difficult steps first, then work backwards. This also give the most practice repetitions to the most difficult steps.

The best solution is to be the choreographer yourself, and choreograph your sequence with the easiest (yet satisfying) steps in the home stretch.

Here's another approach to creating a lesson plan: Think show-biz, constructing your class like a theatrical production with three acts:

Act 1) Your first impression. You don't get a second chance to make a first impression, and if you get off to a bad start, it will take twice the effort to change their minds.

Act 2) As if writing a good mystery drama, think about which clues they need to know first. And what are the actors' (your students) motivations? How will it resolve? The topic of your play is your dance – which dance steps they need to learn first, and why – but the drama of your dance class has clear parallels to a mystery.

Act 3) The big finale, their final impression, so they leave your class happy and satisfied.

If you're teaching figures for an improvised dance, I recommend staying with one family of variations in a class. For instance, once you teach how

to lead and follow a figure that includes a grapevine, then continue with another grapevine figure, so that students can practice that dynamic. Once they've

experienced grapevines in different combinations, Follows will be better prepared to recognize and respond to them in the future, within variations they'

ve never seen, and Leads will be better at playing with grapevines in new ways. Then in a future class, stay with another element, like pivots or double

outside turns, and develop that one dynamic through several figures.

Once you have your lesson plan, memorize it. Don't bring your notes out onto the floor and start reading from them. Maybe keep your notes on a side table, to skim while they're practicing a step. You always want to assure your students that you know your material completely, backwards and forwards, not reading it from a script.

Teach with your whole mind

There is much more to effective teaching than a good lesson plan. Most of the pointers above are left-brain awarenesses, but I think that great teaching is both logical and intuitive, a perfect balance of left & right brain awarenesses. I prefer to think of this as vertical and lateral thinking  which is different from brain lateralization but similar in some ways. Use both vertical and lateral thinking in each class.

which is different from brain lateralization but similar in some ways. Use both vertical and lateral thinking in each class.

This is not a 50/50 balance, but a 100%/100% total awareness. Both vertical and lateral thinking must be fully engaged for maximum effectiveness.

One aspect of teaching from the right-brain (or lateral thinking) is allowing your intuition of the moment to have an equal voice with your lesson plan. Follow your hunches when they differ from your lesson plan, rather than following the plan slavishly.

To access the right brain, relax. Possibly meditate right before a class, if that works for you, or just sit and quiet your mind. You will then be noticeably more observant of how the class is doing, not stuck with your mind in your lesson plan.

Truly watch the dancers to see what they're not getting. This is like being a good listener in a conversation. Don't just follow a formula or plan. Effective teaching is like good partnering, in that it's simultaneously leading and following. Teaching is more leading than following, but you still must be observant and keenly perceptive.

Truly watch the dancers to see what they're not getting. This is like being a good listener in a conversation. Don't just follow a formula or plan. Effective teaching is like good partnering, in that it's simultaneously leading and following. Teaching is more leading than following, but you still must be observant and keenly perceptive.

I've often been asked, "What percentage of the time do you follow your lesson plan, and what percentage do you improvise?"

I improvise all of the time, 100%, based on a solid lesson plan with several backup plans. In other words, our highest priority is watching the class to see what they're getting, at what pace, inserting unplanned details to fix problems, skipping over details which they obviously already have and don't need pointed out. Be 100% prepared (your lesson plan), then 100% observant of how the class is really going, and spontaneously ready to change the plan as needed.

Willam Christensen, founder of the San Francisco Ballet, said that a syllabus makes a bad teacher better, but a good teacher worse. Good point, but I recommend doing both. Prepare a syllabus (lesson plan) as a guideline, then modify it as you teach the class, as needed.

Timing of a class or workshop

These pointers apply both to creating a lesson plan (vertical thinking) and in-class spontaneity (lateral thinking):

Be a clock watcher. Start and end classes on time. Your students may have another class to go to after yours and will rightfully resent your making them late.

Be a clock watcher. Start and end classes on time. Your students may have another class to go to after yours and will rightfully resent your making them late.

Going overtime shows your students that you're disorganized, and can't form a workable lesson plan (see gaining respect of your students below). You may believe that teaching overtime demonstrates your enthusiasm for the material, but in your students' eyes, it only looks like poor planning.

In planning a class or course, make sure that you don't try to cover too much material, or too little. Actually, don't worry about planning too little. Most beginning teachers make the mistake of trying to cover too much material in a class.

In planning a class or course, make sure that you don't try to cover too much material, or too little. Actually, don't worry about planning too little. Most beginning teachers make the mistake of trying to cover too much material in a class.

Make sure each class or topic is brought to a satisfying closure.

On the other hand, if a dance is taught over several days, it's sometimes more effective in the long run to end a class with a difficult challenge, promising to finish (or even fix) it the next day. This unresolved difficulty sticks in their mind, like your tongue which can't stop probing a cavity, and their mind stays with it overnight. This often makes the next day's class more successful.

In planning a day-long workshop, be aware of their relative energy/awakeness level. They may be ready for challenging material first thing in the morning, physically refreshed but sleepy after lunch, and both mentally overloaded and physically exhausted by the end of the day, especially after 4:30 pm.

In an all-day workshop, brain-fade tends to set in at the two-hour mark, even in the morning. Make sure you have a plan to prevent attention from wandering at that time.

The first class of the day can easily be 75 or even 90 minutes long. But schedule afternoon classes to be shorter, maybe 60 minutes each, when their attention span shortens. Another way to enliven the mid-afternoon slump is with humor.

Don't lull them to sleep with slow material at the end of the day. The best choice for the last period is something physically lively, but mentally easy.

Presentation of yourself

Authenticity is the source of true authority. Your credibility is directly correlated to the students' perception that you're genuine. Some teachers fall short because they attempt to project an image of something which they are not. What you are always communicates more powerfully than what you say.

Be more interested in your student's success than your own image. Don't grandstand. The class is about them, not about yourself.

Be more interested in your student's success than your own image. Don't grandstand. The class is about them, not about yourself.

But, on the other hand, realize that your reputation is important to them in one respect: they want to know that you are knowledgeable, and that taking your class is worth their valuable time. You need to gain their respect. Being overly modest or self-deprecating can be just as bad as acting self-important and boastful, because it may raise doubts in their mind about their decision to take your class. "Did I make the wrong choice? This teacher is not very confident. Maybe I should have taken that other class instead."

Your body language should convey confidence and security with the material. Don't fall apart when you err. Don't be overly defensive of your image when you make a mistake, but take it in good-natured stride. Be honest about what you don't know.

But don't be apologetic about your teaching. (I once heard a teacher say, "I imagine many of you won't come back tomorrow.")

This is different from advising, "Don't apologize." As mentioned, if you mess the class up, yes, admit it, rather than vainly trying to cover for it, or blaming something else. You can be both confident and authentic, without any conflict between the two.

Balance authority with a relaxed atmosphere, to help set them at ease.

Balance authority with a relaxed atmosphere, to help set them at ease.

Why set them at ease? Because as mentioned above, they'll be happier and they'll learn much faster if they're in their comfort zone, or a reachable step beyond it.

Voice projection

Speak audibly — clearly and loudly without shouting. Never be shrill.

Speak audibly — clearly and loudly without shouting. Never be shrill.

In a large room, also speak a little more slowly, because reverberation muddles fast speaking.

Use animated tones, without droning. Use contrast. Allow humor, or at least be good-natured.

Use animated tones, without droning. Use contrast. Allow humor, or at least be good-natured.

But I still prefer to be fairly relaxed, not animated to the point of being hyperactive. I recommend a tone of relaxed authority. Remember, you want to let your students stay in their comfort zone. Anxiety interferes with the learning process. But you can't avoid the fact that the process of learning a new dance does push your students, often resulting in some anxiety and frustration, so your calm and reassuring warm tone of voice is important.

Articulate your words – don't mumble. Enunciate, but without straining your face, mouth or neck at all.

Articulate your words – don't mumble. Enunciate, but without straining your face, mouth or neck at all.

A good enunciation exercise is to vocally over-articulate the beginning of the alphabet just before you head into the class. I do this to break out of my habitual everyday voice, into the articulated classroom voice.

Shouting in a large room will strain your voice and you'll soon be hoarse. Do voice exercises before teaching a large class, to preserve your voice. A good exercise is to repeatedly voice a relaxed descending yawn (out in the hallway, before the class).

Use a wireless microphone for a class of more than 40 or 50 people, to preserve your voice and to be heard.

If they can't understand you (mumbling), or can't hear you (talking too quietly), they will assume that what you're saying must not be important, and they won't pay attention.

If they can't understand you (mumbling), or can't hear you (talking too quietly), they will assume that what you're saying must not be important, and they won't pay attention.

Your choice of words: quantity

Don't talk too much. Be efficient with your words. Choose only a few of the most effective words — those which are vivid and evocative yet precise.

Don't talk too much. Be efficient with your words. Choose only a few of the most effective words — those which are vivid and evocative yet precise.

1) They would rather spend more time practicing their dancing, and less time listening to you talk.

2) They need to process the information in their minds, which can't happen unless there are quiet moments to think through what you said.

3) Minds saturate after a barrage of too many words, and their minds start blocking you out.

4) Whether you like it or not, your students are accustomed to getting information very quickly, through broadcast media and the Web, so they get very impatient with long-winded explanations. You can't change them, so work with this to become a more effective teacher.

Yes, you have to convey your information with words, but use the fewest words possible — those which efficiently convey both the details and the spirit of the dance.

This includes not counting while the music is playing, "1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8," nonstop during the music. Yikes! Your students can count just fine without you. Many students complain about this one. It's annoying.

Another verbal barrage that students often find annoying is a constant, "C'mon you can do it! Go! Go! You're doing great!" cheerleading, non-stop for an hour. Enthusiasm and encouragement are fine of course, but any non-stop barrage of words will soon be blocked out, as students need to think through what they're doing. Then they'll miss something important, real information buried in the cheerleading, because they've switched you off.

If you ever feel like you've been talking a little too long, the truth is that it's already been far too long. Why? Have you ever driven to someone's house for the first time, following directions of turns and landmarks, and you thought it took a fairly long time to get there? Then the next time you drive there, once you know the way, it seems much shorter. It's really the same time, but it feels half as long, once you know the way. Why? Once you know where you're headed, you have the destination visualized. Your mind is already there, so it seems shorter.

If you ever feel like you've been talking a little too long, the truth is that it's already been far too long. Why? Have you ever driven to someone's house for the first time, following directions of turns and landmarks, and you thought it took a fairly long time to get there? Then the next time you drive there, once you know the way, it seems much shorter. It's really the same time, but it feels half as long, once you know the way. Why? Once you know where you're headed, you have the destination visualized. Your mind is already there, so it seems shorter.

It's the exact same dynamic with talking. You already know the way (i.e., you know what you intend to say) but your class doesn't. This is their first time down that road, and it can seem like it's taking forever (your talking, that is), just as you're thinking the opposite – "this isn't taking too long to say." Who is right? They are.

Your choice of words: quality

Be both a poet and a technician. Convey the subjective spirit as well as analytical technique. Be inspirational. You teach it digitally (linearly, one aspect at time) then they dance it in analog. Convey both.

Provide precise degrees of movements when applicable — length of steps, degree of turn or turnout, etc.

But don't overspecify when flexible adjustments must be made to accommodate partnering, or when you're teaching a dance which favors individuality. Unnecessary specification is one of dancers' pet peeves.

Don't forget the other physical aspects of a dance beyond footwork: partnering, quality of movement, energy levels, posture, what to do with free hands, facial expressions, flow of movement, etc.

Don't forget the other physical aspects of a dance beyond footwork: partnering, quality of movement, energy levels, posture, what to do with free hands, facial expressions, flow of movement, etc.

Be consistent in your terminology. If a step has five different names among different schools or traditions, pick just one and stay with it. Using multiple terms may only confuse your students.

If you want them to remember the name of a dance or step, have them say a new term audibly. This sends the word through a different part of their brains, from merely hearing it, and thus helps retention.

Basic Pedagogy 101: Repeat questions before answering them, as many questioners speak too quietly to be heard by the other side of the room.

Point out and demonstrate what you liked seeing (even if you only saw a hint of it). Opt to speak in the positive more often; in the negative less often.

Try to maintain the anonymity of those who do a step incorrectly. Be discreet and maybe mention it privately later. But you may point out the individuals who are doing it well.

Tell why a step is done this way. Logic always makes a better and more lasting impression than arbitrary rules, or saying, "because that's the way my teacher taught it."

Tell why a step is done this way. Logic always makes a better and more lasting impression than arbitrary rules, or saying, "because that's the way my teacher taught it."

But don't make up bogus answers. Why not? Because today, people (especially young people) are tired of hype, and are increasingly adept at spotting and dismissing false reasoning. Authenticity is the source of true authority.

Conditional teaching. Experimental research, conducted over 25 years, has proven that when your students are presented with any facts as absolute truths, they tend to use the material thoughtlessly, often making bad, inappropriate or limited decisions. But when they're presented with the same information in a conditional way ("Maybe it's so, but maybe it's also this other way"), they process the information, and use the information, in smarter, more effective, and more creative ways, and also enjoy it more.

Read the page on Ellen Langer's research and findings here. This can have a huge impact on the effectiveness of your teaching.

Team Teaching

Sometimes a class is taught by a Lead/Follow couple, who both speak, sometimes equally. The reasons are usually to offer an additional viewpoint, and to not marginalize one of the partner's roles.

This arrangement can be effective when done well, and problematic when it's done badly.

The most common problem with two-voice teaching is if it doubles the talking time, without adding enough new information to justify the additional non-dancing time, thereby violating one of the most important teaching guidelines. Have a system in place to divide which of you will make which half of the necessary comments, without any repeats.

If you're team-teaching with a partner or collaborator, never rephrase what they just said, even if you think you can say it better. Your slight "improvement" in phrasing doubles the talking time... not a very effective ratio. Just as you're starting to think, "I would say that differently..." immediately replace that thought with, "...but that's good enough for now."

If you're team-teaching with a partner or collaborator, never rephrase what they just said, even if you think you can say it better. Your slight "improvement" in phrasing doubles the talking time... not a very effective ratio. Just as you're starting to think, "I would say that differently..." immediately replace that thought with, "...but that's good enough for now."

Even worse, team-teaching can lead to one person confirming what the other just said. Have you ever experienced this? She finishes saying something about the step, and he can't let it stand without his approval, adding yet more words to the class like, "Yes I agree, blah blah blah."

It's called "mansplaining" and the women in the class usually resent it. The class doesn't need to know that you agree with her. They assume you do, since you're a team, and they want to dance, not listen to more words.

The approver usually thinks he's complimenting his partner by adding his approval, but instead it's an insult to imply that her words cannot stand alone without his approval. (Does this comment seem gender-biased against men? No, it's based on too many bad examples.)

Another disaster is when both count and/or talk while the music is playing, each with different words, at the same moments. Then if each has a microphone, the two voices mix into unintelligible mush over the speakers.

Effective team teachers usually plan in advance who is going to say what, with one perfect thread of information coming from two alternating voices. A few rare team-teachers have a great sense of this pacing without planning in advance. But unfortunately team teaching can also make a class less effective than a single voice, if it's not done well.

Bottom line: Never lose sight of your primary goal, for your students to grasp the material as effectively and efficiently as possible. Your students are smart – they know that a single voice isn't marginalizing any gender or role, and anyone can accurately describe both Lead and Follow pointers. They're there to learn dancing, and they appreciate a well-paced class, regardless of who is talking.

Pace of the class

Don't rush your students. Make sure they have a solid foundation before moving on. If you're afraid of boring them, find other ways to educate or entertain them, rather than just feeding them more steps.

On the other hand, keep the pace of your class moving. Don't let it get bogged down. Don't rush them, but don't bore them either. Talking too much is boring. They want to move, not stand around listening to you talk.

On the other hand, keep the pace of your class moving. Don't let it get bogged down. Don't rush them, but don't bore them either. Talking too much is boring. They want to move, not stand around listening to you talk.

Then when you have something important to say for a few minutes, let them sit down to listen.

One of my solutions to this problem is to skip the classroom discussion of a dance's history and significance, then e-mail this information to my students within the day. But this only works if you have all of your students' e-mail addresses.

Too fast? Too slow?

The best way to keep the pace moving is to change partners, if you're teaching a couple dance form. It's amazing how quickly the group will equalize the combined skill of individuals. Those who have it will show those who don't, Lead or Follow, experienced or newcomer. The couples who don't change partners often keep repeating the same mistake over and over, with no feedback from someone who has succeeded with the figure.

I've often been asked another pacing question, "How much individual attention do you give in a class?"

This isn't a rule, but my personal priority is to care for the greater group. One of my pet peeves is a teacher in a large class spending five minutes working with one individual or couple who has a problem, while 98% of the class stands around bored.

But sometimes you can see that an individual's difficulty or confusion might be true for others too, so you can address that point to the entire class. I tell my students this is a "Repair Clinic" only intended for those who are having this specific difficulty. So I tell the class, "If you're not having this problem, don't fix it." This is serious, not a whimsical comment. Often you'll make a comment to help someone who is under-rotating, for example, then you'll see someone else, who already had it perfectly, now over-rotating after your comment.

Then unfortunately, you'll occasionally get a student who demands that you stop the class to solve their unique problem, which no one else has. (Some psychiatrists call this behavior a "demanding sense of entitlement"). In those cases, you have to be firm for the good of the class, so that the progress of the other students doesn't get stalled or bogged down.

Sometimes you'll get a couple who refuses to change partners when you ask them to. That's fine, but what often happens is they'll be the only couple who doesn't get a figure, when everyone else has succeeded with the help of their rotating partners. Yes, you guessed it — the non-rotating couple will often demand that you slow the class down just for them.

A related question is, "Do you keep working on the step until everyone gets it?"

No, on the average I go for 90% to 95% of the class. The remaining few will usually be helped by their partners who already got it. And the few who are exceptionally slow learners already know they're slow, and would rather that you not make a fuss for them.

Teaching experienced dancers

I'm sometimes surprised to see a professional dance teacher who apparently hasn't thought through the difference between teaching beginning versus experienced dancers. Where do I see this most clearly? In specifying personal style. Beginning and advanced dancers have very different needs and wishes in this area.

When teaching beginners, who are a clean slate, of course you'll teach them the version you think is best, with all of the stylistic details for your preferred form.

But when your students have been dancing for years or decades, they've already developed their personal style, or maybe they've mastered a different teacher's style. This is now who they are. Fred Astaire, among many, wrote this is a good thing. (click for a short quote)

First, they're probably happy with the dancer they've become, and they're taking your class to learn more useful variations and partnering tips from you, not dismantle the dancer they've become. Secondly, they probably couldn't change their personal style if they tried.

The aware teacher will work from this platform (their personal style), giving their experienced students useful new material for them to integrate into their dancing. The unaware teacher will dismiss their students' accumulated style as "incorrect" and attempt to tear it down, hoping to rebuild their student back up in the teacher's preferred style. That's not going to happen! A one-hour class will not undo twenty years of their dancing in a different style. If you attempt to do that, they'll think, "I can't learn from this teacher!" and not come back. And they'll justifiably resent the disrespect of a teacher dismissing their personal style.

Now if they've signed up for a lifetime of private lessons to learn your style, that's different. But this section addresses dance classes or workshops.

You may find it difficult to be patient with experienced dancers who appear to be "doing it wrong," which often means they're merely dancing in styles different from your preferred style. So how should you respond? (A) Dismiss their dancing style, making them wary, defensive or resentful? Or (B), see the class from their point of view. Why are they taking your class? Probably to learn new figures and become better dancers, based on the dancers they are.

I recommend approach B. Allow them to keep their experience and personal style as their platform upon which to build improvements. If you wish to introduce your stylistic preferences, present them as "try this out" options, instead of "you're doing it all wrong" rules. Inspire, don't reprimand. They'll be much happier, meaning they'll learn better (comfort zone). And they'll come back to your second class.

Aging teachers and/or students

As a teacher, you don't have to appear young or youthful. Maturity commands respect. However students unconsciously pick up our most subtle stylings, and if you start moving in an elderly way, so will your students. You can't just suggest, "Do what I say, not what I do." The way you demonstrate a dance is important. (If you're not feeling elderly yet, then be preemptively aware of the ways in which your movement limitations may affect your students some day.)

The good news is that your dancing skills will enable you to walk and move in a younger manner. You know that dancing is acting, so you can mostly act like the movements of a younger dancer, to a certain extent. Here's how...

Study the way that the elderly walk. Watch closely and then imitate their walk. Specifically, you'll see (1) head slouched a little forward, (2) shoulders slightly hunched up, (3) elbows pinned back (that's an important one), (4) limited range of head and arm motion, (5) a shuffling gait on flat feet. Try it – practice that exactly, so you know how it feels. Now reverse all of those. (1) Head tall but not stiff, (2) shoulders down, (3) elbows at your side, not even slightly pinned back, (4) animate your head and arms, (5) stride like a younger person, on the balls of your feet.

Try different strides. The next time you're walking down a sidewalk (maybe when no one is watching) try the John Travolta strut from Saturday Night Fever. Try a hip-hop stride, not to be a poseur, but to expand your range of motion. Loosen up and put a spring in your step. Then keep a little bit of that animation whenever you walk, move, or teach your dance class.

You can take this further by doing stretches every day, yoga and/or Pilates.

If aging or an injury has limited your range of motion permanently, train a younger dancer or couple to be your class demonstrator(s). Your students need a visual prototype, not just your words.

Tempo warning: There may come the day when you think to yourself, "That music feels too fast. I think I'll slow it down for them." Or, "I can't believe I've been teaching it that fast all of these years!" No, the music isn't too fast; you're just slowing down. If your class is comprised of younger people, don't slow the class down to a tempo which works for an older teacher.

Conversely, be aware of the movement limitations of the older dancers in your class. Some dance groups are an aging population — the same dancers getting older every year, for decades. In that case, modify your material to be achievable and satisfying for their age range, which may mean lowering the impact level, slowing the tempo, and simplifying memorization tasks. Remember, you don't want to push them too far out of their comfort zone. You can still teach new and challenging material, but not challenging to the point of frustration or injury.

Music

When using recorded music, have complete technical expertise with the CD player, iPod, iPad, phone or laptop that you'll be using. Avoid using a machine you're unfamiliar with, or come in early to get to know it.

Select all of the music for your class ahead of time. It takes time to find a perfect track for a particular step, with the right tempo, quality, energy level, and emphasis on the right beats. Some teachers make their students stand around as they start to fumble through their music collection searching for a good track. It's even more embarrassing if the track you chose doesn't work well, and you have to stop it and start searching again. Go through that process before class.

Select all of the music for your class ahead of time. It takes time to find a perfect track for a particular step, with the right tempo, quality, energy level, and emphasis on the right beats. Some teachers make their students stand around as they start to fumble through their music collection searching for a good track. It's even more embarrassing if the track you chose doesn't work well, and you have to stop it and start searching again. Go through that process before class.

If you play CDs, a more specific tip is to buy a red grease pencil at a hardware store, normally used for marking glass, and write the track number of your pre-selected music on the CD or case. After class you can erase it with a tissue.

List your pre-selected tracks in your lesson plan notes.

Know how to count into the music. Use the same number of preparatory counts each time. I prefer to count into a dance just as a musician would, saying something like, "five, six, ready, and..."

Know how to count into the music. Use the same number of preparatory counts each time. I prefer to count into a dance just as a musician would, saying something like, "five, six, ready, and..."

But do give them some warning! It's amazing how often teachers just start dancing a step without warning, and expect the class to read their mind that they were going to start. Yes, your students can start a moment late and catch up with you, but they'd much rather know when you're going to start.

"...than you would begin a sentence in the middle, or..."

???

Did that make sense to you? No, and neither does starting and stopping your recording arbitrarily in the middle of a musical phrase. When playing your recorded music, allow the musical phrases to finish, as live musicians would do. Musicians would never start and stop in mid-phrase, any more than you would begin a sentence in the middle, or stop speaking halfway through a sentence. I recommend that you play your recorded music the same way.

This guideline isn't marked as essential, but you should realize that your musical phrasing of recorded music demonstrates your respect for the music. So if you start and stop your music arbitrarily in mid-phrase, it tells your class that you don't care very much about music.

Most teachers teach a dance step tacet (without music) so they can be heard clearly, and then after the class has practiced it a few times, they put on the music. It's the natural progression. However...

When you do this, you must make sure that you have brought your teaching tempo up to the same as the tempo of the music that you're about to play. It's a huge mistake to teach a step at a slow tempo, then put on music which is significantly faster, guaranteeing frustration or failure among many of your students.

When you do this, you must make sure that you have brought your teaching tempo up to the same as the tempo of the music that you're about to play. It's a huge mistake to teach a step at a slow tempo, then put on music which is significantly faster, guaranteeing frustration or failure among many of your students.

A helpful hint is to hear the tune that you're about to play in your head, while you're still teaching it tacet. With a little practice you'll be able to bring the class up to the exact tempo of the music before you play it. This way, the music supports their dancing, at just the right tempo, instead of pressuring your students.

Changing tempo: Your music player may have tempo control, which is an important tool for teaching dance. We usually need to start a dance at a slower tempo, then let the speed pick up with practice. My favorite method uses the Amazing Slow Downer software available online for both Mac and PC. This is the highest quality software I've seen for slowing down or speeding up the tempo without changing the pitch. If you play music from a laptop, you can do this in real-time, in class.

I don't use a laptop for my class music so I pre-record the music, at several tempos slowed by Amazing Slow-Downer. Some CD players change tempo without changing pitch, but all firmware solutions that I've seen sound watery and choppy when slowed more than 8%. Amazing Slow Downer retains realistic fidelity when slowed 50%. Speeding up music is easy with software or firmware; it's the slowing down with fidelity that's hard.

More on ideal dance tempos is here.

When you're thinking through your back-up plans, include possible problems with music. How might the sound go wrong? What components or connectors for the sound system might be missing? When teaching in a new space, consider bringing a backup sound system (even if just a boom box), extra batteries for a wireless microphone, and extra audio adaptors for other's sound systems.

Working with live music is a full discussion in itself, but the short version is to respect your musicians, never treating them like hired help, or worse, as an equivalent to canned music. Let your students applaud them at the end of class. But you know this, so I'll skip that topic for this page.

Spatial arrangement

If teaching to a group in the round, be sure to show a step at several angles, for those who couldn't see an important detail from their side of the room. This may also avoid some mirror-image problems. Don't wait for them to request this. If they have to ask to see it from their viewpoint, you've already failed to consider their point of view.

Dance teachers often have to deal with the mirror-image problem, when a student facing you has to step or gesture to their right, as you're showing it to your right, which is the opposite of a mirror image. One solution is for you to mirror the step yourself as you face them, gesturing to your left as you mean (and say) "right".

A second solution is to teach with students in a large circle and have an assistant on the other side, facing you. Ask your students to follow the person in front of them.

A third solution, if they're in a circle around the perimeter of the room with you in the middle, is to have them all turn a quarter to their right, toward Line of Dance, asking them to follow most of those ahead of them. They can clearly see both you and those ahead of them.

Another tradition is for the teacher to face a large mirror, with the students behind, also facing the mirror. It's not ideal to turn your back to your students, but they can see your face in the mirror.

When Lead's and Follow's steps differ significantly in partnered couple dancing, sometimes it's effective to have all of the Leads stand behind the Lead teacher/partner and all Follows behind the Follow teacher/ partner. After teaching the step(s), let them walk forward to find a partner on the other side.

Miscellaneous

Don't forget warm-ups and stretches when necessary.

In partnered couple dancing, don't forget to change partners every five minutes or so. Students learn much faster when they change partners, with the extra benefit of learning how to dance with people of all shapes, sizes and experience levels. But many dancers come with a favorite partner, who they dance with first, so I like to return them to their first partners once in a while, and then again for the last dance of the class.

Consider providing handouts and music recordings where applicable. Syllabi can also be put online, and I sometimes e-mail my students the dance descriptions after a class.

Be generous in your appraisal of other dancers and instructors. This is not only considerate of others in your field, but it's good for you too — everyone knows that only the most confident teachers are charitable toward their competitors.

An ideal that I value is to use a dance to illustrate a higher concept, such as partnering, traditions, ways to be a better person, new ways of using the mind and body, analogies to personal relationships, or something philosophical, beyond the steps. But this is optional.

It's great if you can make your class convey more than just steps, but it's not necessary.

Have a greater concern with your students' progress and comprehension than in enhancing your own reputation. This dedication must be sincere, and not just an act. Effective teaching is like good dance partnering, in that it's primarily dancing for your partner's success, rather than showing off yourself.

This concern for your students is also a sign of maturity. Small children constantly clamor, "Look at me Daddy! Watch me Mommy!" Then we grow up, and we (hopefully) mature into valuing others' happiness and progress. The few teachers who don't understand this are quite obvious to their students, as self-absorbed grandstanders more interested in displaying their greatness than in helping their students learn the material.

But I know you're completely devoted to your students' success, or else you wouldn't have made it to the bottom of this page.

Teaching makes you smarter

Take a look at this page, Use It or Lose It: Dancing Makes You Smarter. It's a report on several studies which show that rapid-fire decision-making maintains or increases your intelligence as you age. Teaching a class involves even more rapid-fire decision making than dancing, so it's ever better for you. Then furthermore...

I like R. Buckminster Fuller's definition of genius. In his opinion, genius isn't a mere quantity or capacity, but the combination of rational and intuitive thinking, both left-brain and right-brain, vertical and lateral thinking. And it's the simultaneous use of both kinds of thinking, not exercising linear rational thinking first thing in the morning, then doing something more intuitive an hour later. Genius is being fully rational and fully intuitive at the same time, seeing both the finest details and the overall big picture at the same time.

Teaching a class, in any topic, is one of the ultimate simultaneous combinations of vertical and lateral thinking, as your planning strategies morph with your spontaneous assessment of your students' progress. But as the research shows, it depends on continual split-second decision making, not repeating rote routines. You don't have to be a genius, but to stay smarter longer, don't always follow the same lesson plan. Teach it differently each time, spontaneously making those changes in class. Or teach topics you've never taught before. Challenge yourself. Plan your class thoroughly, then welcome chance intrusions. Every day. Research shows that it will keep you smarter longer.

Overwhelmed?

The human mind can't keep track of a hundred pointers simultaneously so don't even try to achieve perfection in teaching. It doesn't exist. If following some of these guidelines helps your next class be 5% more successful, great. Don't be hard on yourself — it gets better with each class. Allow mastery to develop at its own pace.

But you do have to try. Improving your teaching takes concentration and effort. You can read these pointers, and understand them, and even agree with many of them, but nothing will change until you incorporate them into your teaching. That takes a conscious effort on your part and practice. And don't forget to take lots of notes before and after your classes.

Enjoy the process, every step along the way. Some teachers dwell on the belief that they're not "there" yet, and look forward to the day when they are. No, it's much more rewarding to realize that you are already there, completely immersed in the moment, while also helping others. What could be better? Enjoy it!

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank both the good and bad exemplars in my many years of taking dance classes. I learned equally as much from both.

I'd like to thank my collaborator of the past 35 years Joan Walton, for participating in many discussions about dance pedagogy over the years. It's a fascinating field.

Photo by Jason Chuang.

© Copyright 1986 - 2025 Richard Powers

More thoughts and musings

Stanford Home Accessibility

which means essential, in my opinion. (The most important suggestion here, halfway down this page, has a triple arrow.) Failing to do these may cause a negative impression or confusion in your class.

But most of these guidelines are merely recommendations. They may make a good class better, but omitting them won't hurt a good class.

which means essential, in my opinion. (The most important suggestion here, halfway down this page, has a triple arrow.) Failing to do these may cause a negative impression or confusion in your class.

But most of these guidelines are merely recommendations. They may make a good class better, but omitting them won't hurt a good class.  Don't forget the big picture. In preparing for a class, we tend to get caught up in the smaller details of the steps and patterns, focusing on

the how and forgetting the why. So teachers often find they've finished the class without addressing the larger picture:

Don't forget the big picture. In preparing for a class, we tend to get caught up in the smaller details of the steps and patterns, focusing on

the how and forgetting the why. So teachers often find they've finished the class without addressing the larger picture:  Take charge immediately in a direct, friendly, assertive way. Don't pussyfoot. This is important for new teachers, who are sometimes meek and tentative.

Take charge immediately in a direct, friendly, assertive way. Don't pussyfoot. This is important for new teachers, who are sometimes meek and tentative.  Don't start a class with a lecture. Get them moving right away.

Don't start a class with a lecture. Get them moving right away. Know your audience. Different groups require very different approaches, depending on their dance experience, age range, preferred dance styles, and whether they wish to use your material professionally or recreationally. If you're traveling to a new group, ask your workshop sponsor many questions about their participants ahead of time, so you arrive prepared.

Know your audience. Different groups require very different approaches, depending on their dance experience, age range, preferred dance styles, and whether they wish to use your material professionally or recreationally. If you're traveling to a new group, ask your workshop sponsor many questions about their participants ahead of time, so you arrive prepared.  Take detailed notes on every class you teach, including which concepts (like partnering tips) you mention. When we brainstorm a lesson plan for the first time, all of the details are freshly in our mind during the class, and it goes well. But when we teach that dance the next time, perhaps a year later, most of the details, and how we broke them down, and which concepts we mentioned, have faded from memory. That's when you'll be glad you took detailed notes.

Take detailed notes on every class you teach, including which concepts (like partnering tips) you mention. When we brainstorm a lesson plan for the first time, all of the details are freshly in our mind during the class, and it goes well. But when we teach that dance the next time, perhaps a year later, most of the details, and how we broke them down, and which concepts we mentioned, have faded from memory. That's when you'll be glad you took detailed notes.  Take as many other classes as you can, closely observing what other teachers do that is especially effective or problematical. Take notes on your observations.

Take as many other classes as you can, closely observing what other teachers do that is especially effective or problematical. Take notes on your observations. Plan out every aspect of your class:

Plan out every aspect of your class: This includes developing back-up plans. What kind of additional material should you prepare in case the students turn out to be mostly experienced quick-studies? What if they're slow-learning non-dancers? What if they're a mixture of the two in the same class? And don't forget to bring music for teaching those back-up plans.

This includes developing back-up plans. What kind of additional material should you prepare in case the students turn out to be mostly experienced quick-studies? What if they're slow-learning non-dancers? What if they're a mixture of the two in the same class? And don't forget to bring music for teaching those back-up plans.Here's a little more on students' comfort zone, because I don't want to speed by this important point. Your students will reach their optimum learning pace if they're just a small, reachable step beyond their comfort zone — enough to be stimulated and motivated, but not to the point of feeling pressured or stressed.

In a related point, never EVER lose your temper in class. Period. No exceptions. There are so many reasons why this is critical that it should be too obvious to require explanation. Most of the reasons have to do with losing control of the class. And losing control of yourself. (How can they expect you to control the class if you can't control yourself?) And thus losing their respect. Your anger will also hinder their learning pace by adding anxiety to the class.

In a related point, never EVER lose your temper in class. Period. No exceptions. There are so many reasons why this is critical that it should be too obvious to require explanation. Most of the reasons have to do with losing control of the class. And losing control of yourself. (How can they expect you to control the class if you can't control yourself?) And thus losing their respect. Your anger will also hinder their learning pace by adding anxiety to the class.  Appeal to visual, mathematical, auditory and kinesthetic learners by describing the same step in several ways.

Appeal to visual, mathematical, auditory and kinesthetic learners by describing the same step in several ways. If teaching partnered couple dancing, always have one track of your mind on the Follow role. Many teachers make the mistake of teaching an entire session only addressing what the Lead role does, without offering many suggestions, advice or secrets for Follows to improve their dancing.

If teaching partnered couple dancing, always have one track of your mind on the Follow role. Many teachers make the mistake of teaching an entire session only addressing what the Lead role does, without offering many suggestions, advice or secrets for Follows to improve their dancing.  which is different from brain lateralization but similar in some ways. Use both vertical and lateral thinking in each class.

which is different from brain lateralization but similar in some ways. Use both vertical and lateral thinking in each class.  Truly watch the dancers to see what they're not getting. This is like being a good listener in a conversation. Don't just follow a formula or plan. Effective teaching is like good partnering, in that it's simultaneously leading and following. Teaching is more leading than following, but you still must be observant and keenly perceptive.

Truly watch the dancers to see what they're not getting. This is like being a good listener in a conversation. Don't just follow a formula or plan. Effective teaching is like good partnering, in that it's simultaneously leading and following. Teaching is more leading than following, but you still must be observant and keenly perceptive. Be a clock watcher. Start and end classes on time. Your students may have another class to go to after yours and will rightfully resent your making them late.

Be a clock watcher. Start and end classes on time. Your students may have another class to go to after yours and will rightfully resent your making them late.  In planning a class or course, make sure that you don't try to cover too much material, or too little. Actually, don't worry about planning too little. Most beginning teachers make the mistake of trying to cover too much material in a class.

In planning a class or course, make sure that you don't try to cover too much material, or too little. Actually, don't worry about planning too little. Most beginning teachers make the mistake of trying to cover too much material in a class.

Be more interested in your student's success than your own image. Don't grandstand. The class is about them, not about yourself.

Be more interested in your student's success than your own image. Don't grandstand. The class is about them, not about yourself.  Balance authority with a relaxed atmosphere, to help set them at ease.

Balance authority with a relaxed atmosphere, to help set them at ease.  Speak audibly — clearly and loudly without shouting. Never be shrill.

Speak audibly — clearly and loudly without shouting. Never be shrill. Use animated tones, without droning. Use contrast. Allow humor, or at least be good-natured.

Use animated tones, without droning. Use contrast. Allow humor, or at least be good-natured.  Articulate your words – don't mumble. Enunciate, but without straining your face, mouth or neck at all.

Articulate your words – don't mumble. Enunciate, but without straining your face, mouth or neck at all.  If they can't understand you (mumbling), or can't hear you (talking too quietly), they will assume that what you're saying must not be important, and they won't pay attention.

If they can't understand you (mumbling), or can't hear you (talking too quietly), they will assume that what you're saying must not be important, and they won't pay attention.

Don't talk too much. Be efficient with your words. Choose only a few of the most effective words — those which are vivid and evocative yet precise.

Don't talk too much. Be efficient with your words. Choose only a few of the most effective words — those which are vivid and evocative yet precise. If you ever feel like you've been talking a little too long, the truth is that it's already been far too long. Why? Have you ever driven to someone's house for the first time, following directions of turns and landmarks, and you thought it took a fairly long time to get there? Then the next time you drive there, once you know the way, it seems much shorter. It's really the same time, but it feels half as long, once you know the way. Why? Once you know where you're headed, you have the destination visualized. Your mind is already there, so it seems shorter.

If you ever feel like you've been talking a little too long, the truth is that it's already been far too long. Why? Have you ever driven to someone's house for the first time, following directions of turns and landmarks, and you thought it took a fairly long time to get there? Then the next time you drive there, once you know the way, it seems much shorter. It's really the same time, but it feels half as long, once you know the way. Why? Once you know where you're headed, you have the destination visualized. Your mind is already there, so it seems shorter. Don't forget the other physical aspects of a dance beyond footwork: partnering, quality of movement, energy levels, posture, what to do with free hands, facial expressions, flow of movement, etc.

Don't forget the other physical aspects of a dance beyond footwork: partnering, quality of movement, energy levels, posture, what to do with free hands, facial expressions, flow of movement, etc.  Tell why a step is done this way. Logic always makes a better and more lasting impression than arbitrary rules, or saying, "because that's the way my teacher taught it."

Tell why a step is done this way. Logic always makes a better and more lasting impression than arbitrary rules, or saying, "because that's the way my teacher taught it." If you're team-teaching with a partner or collaborator, never rephrase what they just said, even if you think you can say it better. Your slight "improvement" in phrasing doubles the talking time... not a very effective ratio. Just as you're starting to think, "I would say that differently..." immediately replace that thought with, "...but that's good enough for now."

If you're team-teaching with a partner or collaborator, never rephrase what they just said, even if you think you can say it better. Your slight "improvement" in phrasing doubles the talking time... not a very effective ratio. Just as you're starting to think, "I would say that differently..." immediately replace that thought with, "...but that's good enough for now."  On the other hand, keep the pace of your class moving. Don't let it get bogged down. Don't rush them, but don't bore them either. Talking too much is boring. They want to move, not stand around listening to you talk.

On the other hand, keep the pace of your class moving. Don't let it get bogged down. Don't rush them, but don't bore them either. Talking too much is boring. They want to move, not stand around listening to you talk. Select all of the music for your class ahead of time. It takes time to find a perfect track for a particular step, with the right tempo, quality, energy level, and emphasis on the right beats. Some teachers make their students stand around as they start to fumble through their music collection searching for a good track. It's even more embarrassing if the track you chose doesn't work well, and you have to stop it and start searching again. Go through that process before class.

Select all of the music for your class ahead of time. It takes time to find a perfect track for a particular step, with the right tempo, quality, energy level, and emphasis on the right beats. Some teachers make their students stand around as they start to fumble through their music collection searching for a good track. It's even more embarrassing if the track you chose doesn't work well, and you have to stop it and start searching again. Go through that process before class. Know how to count into the music. Use the same number of preparatory counts each time. I prefer to count into a dance just as a musician would, saying something like, "five, six, ready, and..."

Know how to count into the music. Use the same number of preparatory counts each time. I prefer to count into a dance just as a musician would, saying something like, "five, six, ready, and..."  When you do this, you must make sure that you have brought your teaching tempo up to the same as the tempo of the music that you're about to play. It's a huge mistake to teach a step at a slow tempo, then put on music which is significantly faster, guaranteeing frustration or failure among many of your students.

When you do this, you must make sure that you have brought your teaching tempo up to the same as the tempo of the music that you're about to play. It's a huge mistake to teach a step at a slow tempo, then put on music which is significantly faster, guaranteeing frustration or failure among many of your students.