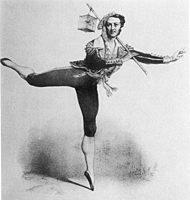

Early 19th Century Ballet

Early 19th Century Ballet

The first four decades of the 19th century represent a vital period in the history of ballet. During those years

important aspects of Baroque dance were preserved; the content of the ballet class as we know it today was

established; and dancers were trained and prepared for the technical challenges ushered in by the two most

important productions of the Romantic ballet era—La Sylphide (Paris, 1832) and Giselle (Paris, 1841).

Pierre Gardel, balletmaster at the Paris Opéra from 1787 to 1827, successfully maintained the ballet enterprise through

the tumultuous years of the French revolution and its aftermath. By 1799, the ballet was officially recognized

as a separate but vital entity at the Opéra. Thus, as in the preceding century, most dancers in the 19th century

continued to regard Paris as the locus of superior dance training, performances, and productions.

Ballets continued to be viewed as danced dramas, the term "ballet-pantomime" replacing the earlier term, "ballet

d'action." Rehearsal scores, répétiteurs, contained detailed information for the mimed gestures and expressions,

allied closely to the musical notes and phrases in the score. Dancing mostly occurred in extended divertissements,

often associated with celebratory scenes. Pas de deux, pas de trois, pas de cinq, etc. were indicated in the

score but without details of steps. A local balletmaster, having obtained the score, could devise his own

choreography of a well-known ballet, perhaps based on his memory of a Paris production, while maintaining the

integrity of the ballet by conforming to the details of the storyline.

Following this tradition, August Bournonville, using a newly commissioned score, rechoreograhed Filippo Taglioni's

ballet La Sylphide for the Royal Danish Ballet in 1836, a version which remains a staple of the company's

repertory. The RDB also has retained a version of the Pas de Vestale, a pas de deux created by Gardel in 1807

for the opera La Vestale.

The complete choreographic notes and the music for Gardel's famous pas de deux are among other valuable

theatrical dance materials compiled between 1820 and 1836. From these sources we learn how theatrical pas,

the entrées for one or more dancers, were structured as well as the ballet vocabulary employed. Written by

dancers who also were teachers, these sources reveal the ballet tradition as it developed not only in Paris but

also in other major dance centers.

Of particular importance is what the written sources reveal about the development of ballet technique and

training. The structure of the class, beginning with the elementary exercises—pliés, relevés, battements,

ronds de jambe—are outlined and described in detail. The ports de bras and exercices d'aplomb as described

correspond closely to exercises continued into today in the Cecchetti Methode, the Vaganova tradition, and

the Bournonville School.

Developments in pointe technique—dancing on the tips of the toes—are documented, providing examples of

movements, and the strengthening exercises they required, that were mastered by Marie Taglioni and her

predecessors. Their abilities, often viewed today as "revolutionary," were at the time a logical development

of a dance technique that had long emphasized lightness and elevation. Going from demi-pointe to full pointe

was part of that evolution.

Sometimes viewed as an obscure period in ballet's history, the early 19th century might better be seen as the

continuation of a rich, complex art form, absorbing new developments that would have far reaching impact.

Practitioners from the period have left records of ballet training and choreographies that invite our investigations

and, ultimately, performances.

— Sandra Noll Hammond